Facilities that ask how to transport drums safely must control the full system of drum, pallet, and vehicle. This article explains engineering of the drum–pallet interface, securement methods, and regulatory duties for local and over-the-road freight. You will see how drum type, UN code, pallet design, and load restraint affect stability, leak risk, and legal compliance from dock to delivery. The final section turns these points into a concise best-practice checklist that operations, safety, and logistics teams can apply in daily transport planning.

Engineering The Drum, Pallet, And Load Interface

Engineering the drum, pallet, and load interface is the core of how to transport drums safely. This interface decides whether loads stay stable from filling to final delivery. It links UN drum design limits with pallet stiffness, deck gaps, and restraint methods. A robust interface reduces shift, tipping, and impact damage in both local and over-the-road freight.

Drum Types, UN Codes, And Structural Limits

Drum type and UN code define what the package can safely tolerate in transport. Steel, plastic, and composite drums follow different construction rules, wall thickness ranges, and closure designs. UN codes such as 1A1, 1A2, 1H1, 1H2, 1N1, and 1N2 specify material, head style, and performance level. For non-steel metal drums, 1N1 means non-removable head and 1N2 means removable head.

Regulations set maximum capacity near 450 litres and net mass near 400 kilograms for many UN drums. Welded seams and reinforced chimes keep the shell stable under stacking and tie-down loads. Rolling hoops, when present, must not shift or loosen under vibration or impact. Openings and closures need to stay leak tight under normal transport conditions, often with gaskets.

When planning how to transport drums, engineers must match fill level, liquid density, and expected accelerations to these limits. Overfilling or using the wrong drum type for the product class increases bulging and failure risk. Internal coatings or linings are required when shell material and contents are incompatible. These choices set the safe envelope for palletization and restraint.

Pallet Design, Deck Gaps, And Load Distribution

Pallet design controls how drum loads transfer into truck floors, docks, and storage systems. For 55-gallon drums, guidance required plastic or hardwood pallets with deck gaps below about 20 millimetres. Small gaps reduce local deformation at the chimes and prevent drums from dropping into voids. A pallet or skid must support the full drum footprint and rated mass with margin.

Engineers assess pallet stiffness, deck board spacing, and stringer layout. A stiff pallet keeps the load plane flat and reduces rocking during braking or cornering. Typical best practice keeps three or four drums per pallet, depending on pallet size, to maintain symmetry. Overloading pallets or exceeding rated capacity increases risk of deck failure and sudden drum movement.

Good load distribution places the combined centre of gravity near the pallet centre. Mixed drum sizes on one pallet often create eccentric loads and should be limited. When multiple pallets travel together, operators stack or position them to keep axle loads within vehicle limits. Consistent pallet specifications across a fleet simplify training and inspection.

Drum Grouping, Stacking, And Center-Of-Gravity Control

Grouping and stacking strategy decide how to transport drums without shift or tipping. Drums should remain upright on pallets, with contact rings aligned to share load evenly. Before strapping to the pallet, operators often band drums together into a rigid cluster. This grouping reduces relative movement under vibration and emergency manoeuvres.

Stack height must respect drum stacking test ratings and pallet compressive strength. Many facilities limit palletized drum stacks to one drum layer per pallet in transit. Where vertical stacking is allowed, engineers verify that lower drums can carry the mass of upper tiers. They also check trailer or container headroom and dynamic clearance.

Centre-of-gravity control focuses on three points. First, keep heavy drums low and centred on the pallet. Second, avoid tall, narrow stacks with small base area. Third, align grouped pallets in the vehicle so combined centres of gravity sit close to the vehicle centreline. These rules reduce rollover risk and sidewall impacts.

Operators must also consider partial loads and returns. A single drum on a pallet needs extra blocking or chocking to avoid rolling. Training should explain how small layout changes can shift the centre of gravity by several centimetres. Even modest shifts matter under hard braking or uneven road surfaces.

Protective Slipcovers, Wraps, And Reusable Securing Aids

Protective interfaces between drums and the environment complete the load design. Overpack slipcovers in two-ply or three-ply cardboard shield drums from dents and abrasion. Guidance required these covers to extend over the full pallet footprint and drum height. Vertical banding, usually two bands each way, ties the slipcover to both pallet and drums.

Stretch wrap and shrink film add surface friction and unitize the load. However, wrap alone cannot replace proper strapping or banding. Thin or damaged film allows creep, which slowly loosens stacks during long trips. Engineers specify wrap thickness, number of wraps, and overlap patterns when film is used.

Reusable securing aids reduce waste and improve consistency. Examples include rim clips, corner boards, and strap protectors that spread strap pressure. These devices protect drum paint and labels while maintaining high strap tension. They also help operators place straps in repeatable positions relative to rolling hoops or chimes.

When defining how to transport drums in a specific route, teams should compare single-use wraps and reusable aids. Criteria include load stability, cycle time, waste volume, and damage rates. Reusable systems need clear return logistics and inspection routines. The final interface should deliver stable, inspectable loads with minimal manual rework at each handoff.

Securing Drums For Local And Over-The-Road Shipments

Safe drum securing is the core of any plan for how to transport drums. Local trips and over-the-road (OTR) freight expose drums to vibration, braking, cornering, and impact loads. The securing method must match drum type, pallet strength, and route conditions. Engineers should treat each palletized drum load as a restraint system, not just a stack of containers.

Strapping, Banding Patterns, And Corner Protection

Strapping controls drum movement relative to the pallet and to adjacent drums. Most operators used at least two straps of metal or high-strength plastic for 55 litre to 200 litre drums. Straps should run both transverse and longitudinal where possible to resist acceleration in all directions. Banding patterns must keep the load as one rigid block, not multiple loose groups.

Engineers often apply this sequence when planning how to transport drums on pallets:

- Band drums together as a cluster on the pallet.

- Apply at least two straps over the drum group and under the pallet deck.

- Add vertical bands to tie any top cap or slipcover to the pallet.

Corner protection reduces local stress from straps on drum chimes and edges. Strap protectors or cleats spread the load and limit cosmetic damage. They also increase friction between strap and drum, which helps keep tension during vibration. For OTR freight, corner protection is essential when using high-tension steel banding.

Pallet Load Ratings, Weight Limits, And Overload Risks

Pallet selection must start with the drum mass and the total pallet load. A pallet or skid must support the combined drum weight plus dynamic factors from transport. Typical practice keeps total pallet mass well below the rated static and dynamic load of the pallet. Overloading reduces safety margin against impact, racking, and floor point loads.

When planning how to transport drums by road, engineers should check three limits:

| Limit type | Key check |

|---|---|

| Pallet rating | Total drum mass versus pallet dynamic capacity |

| Vehicle floor | Concentrated load versus floor and deck rating |

| Freight rules | Maximum pallet count and total shipment mass |

Deck design also matters. For 55-gallon drums, gap width under about 20 millimetres reduces local bearing stress on chimes and lowers the risk of denting. Wide gaps can allow chime drop-through, which creates tilt and strap loosening. Engineers should avoid stacking pallets of drums beyond the pallet and vehicle ratings, even if the drums themselves remain within their UN load limits.

Preventing Shift, Tipping, And Impact Damage In Transit

Drum stability in transit depends on friction, geometry, and restraint. Drums should stand upright on flat, clean pallets to maximize base contact. Operators should remove oil, dust, or loose wrap that would reduce friction. Banding and blocking then supplement friction to resist lateral and longitudinal forces from braking and cornering.

To control tipping and shift when deciding how to transport drums, engineers typically combine several methods. Dunnage or anti-slip mats between drum and pallet increase friction. Edge boards or perimeter frames prevent lateral roll-off. Overpack slipcovers in strong cardboard protect against minor impacts and help keep the drum set compact. Vertical banding ties the cover, drums, and pallet into one unit.

Inside trailers or containers, loads need secondary restraint. Load bars, shoring beams, or blocking against bulkheads limit gross movement. Gaps between pallets should be minimal or filled with blocking to avoid run-up distance before impact. For hazardous contents, planners should assume a worst-case emergency brake or cornering event and design restraints so drums remain upright and sealed under those accelerations.

Regulatory Compliance And Hazardous Materials Handling

Regulatory control sits at the core of how to transport drums safely and legally. Engineers and logistics planners must link drum design, filling practices, and paperwork to current dangerous goods rules. This section focuses on TDG style requirements, UN drum packaging, and operator duties that affect daily freight decisions.

TDG, UN Packaging, And Safety Marking Requirements

Transport rules for dangerous goods required UN performance packaging and clear safety marks. UN drum codes defined material, head type, and performance level. For example, non‑steel metal drums used 1N1 for tight head and 1N2 for open head versions. Each code tied to test standards for drop, leak, and stack performance.

Regulations limited capacity and mass. Typical limits for non‑steel metal drums were 450 litres and 400 kilograms net mass. Construction rules demanded welded seams and reinforced chimes. Rolling hoops needed secure attachment without spot welding to avoid weak points under transport loads.

TDG style rules required visible safety marks on at least one drum side or on the overpack. Marks had to stay legible during handling, storage, and transport. Where exemptions applied, shipping names and class marks could replace full labels if visible and correct. For operators searching how to transport drums, correct marks were the first compliance checkpoint.

Filling, Venting, And Compatibility Of Drum Contents

Correct filling and venting reduced leak and rupture risk during local or OTR trips. Regulations tied fill level to liquid expansion at expected temperatures. Overfilled drums could deform or weep at closures during hot weather. Underfilled drums increased slosh and dynamic loads during braking and cornering.

Venting requirements depended on product vapour pressure and gas generation. Tight head drums used small bung vents or pressure relief devices when allowed. Closures needed gaskets or liners that stayed leak tight under vibration and tilt. Rules demanded that closures remained secure under normal transport conditions.

Chemical compatibility between contents and drum material was critical. If the shell metal or plastic reacted with the product, internal linings or coatings were mandatory. Engineers checked resistance charts and approval letters before selecting a drum type. This avoided wall thinning, embrittlement, or coating failure during long storage and transport cycles.

Exemptions, Documentation, And Carrier Responsibilities

TDG style frameworks included quantity‑based exemptions that affected how to transport drums in mixed loads. One common model allowed simplified rules where total dangerous goods mass stayed at or below 500 kilograms per vehicle. Small means of containment up to 30 kilograms each, or compliant drums, could qualify if other conditions were met. Goods that needed an emergency response plan or special temperature control never qualified.

Even under exemptions, documentation duties remained. Shipping papers had to list proper shipping names, primary hazard classes, and the count of marked packages by class. Documents had to ride in the cab or other defined locations for road, rail, or vessel transport. Missing or wrong papers created both safety and legal risk.

Carriers held clear responsibilities. They had to verify marks, labels, and documents before accepting drums. They also needed trained staff who understood segregation rules and incident actions. Using a carrier without dangerous goods competence increased the chance of mis‑routing, poor load building, and weak incident response. For shippers, carrier vetting was a core step in any compliant drum transport plan.

Summary Of Best Practices For Industrial Drum Transport

Safe drum transport depends on a controlled interface between drum, pallet, and vehicle. Operators who ask how to transport drums should combine sound engineering, clear procedures, and strict regulatory compliance. The goal is stable loads, compliant markings, and zero leaks from filling plant to destination.

From an engineering view, use pallets or skids that support the full drum footprint and weight. Keep deck gaps small to limit local bearing stress and prevent chime damage. Position drums upright and group them in tight patterns to keep the center of gravity low and centered. Avoid overloads; respect pallet and vehicle ratings with adequate safety margins.

Securing methods must resist vibration, braking, and cornering. Use suitable straps or bands with corner protection and, where needed, overpack slipcovers or wraps. Verify that securing devices maintain tension for the full route, including over-the-road freight. For sensitive or hazardous loads, add secondary containment and spill kits near loading and unloading areas.

Regulations for dangerous goods require approved drum designs, compatible closures, and correct safety marks. Fill levels, venting, and internal coatings must match the product and journey conditions. Documentation, exemptions, and carrier duties sit within formal TDG and UN frameworks and changed over time. Future practice will likely blend smarter load-securing devices, reusable securing aids, and better digital tracking, but conservative loading and disciplined handling will remain the core of safe drum transport.

,

Frequently Asked Questions

What equipment is used to transport 55-gallon drums safely?

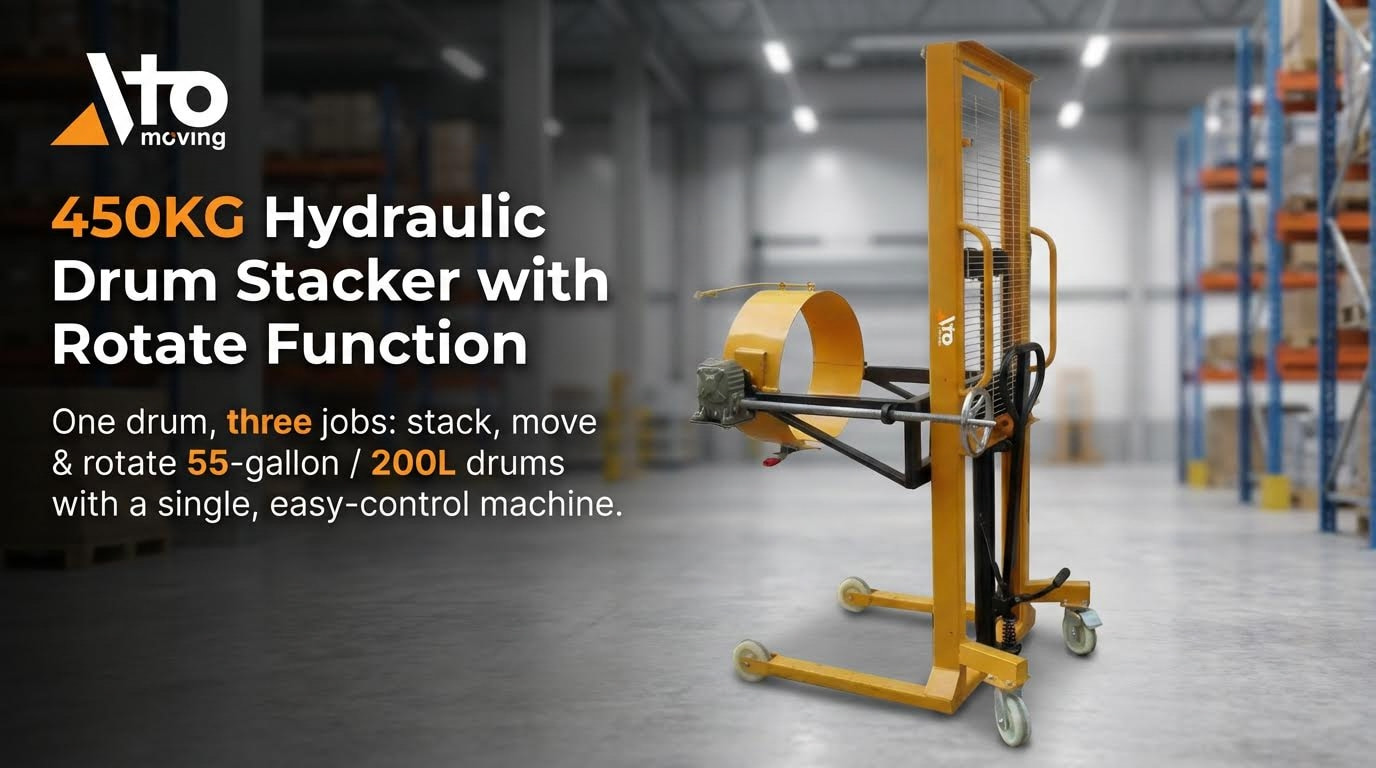

To transport 55-gallon drums safely, it’s important to use the right equipment. Forklifts, pallet jacks, and drum dollies are commonly used in material handling to move these heavy containers. Attempting to roll or lift them manually can lead to accidents and injuries. Drum Handling Guide.

How do you protect a drum set during transportation?

When transporting a drum set, protection is key to avoid damage. Line the inside of the drums with cardboard and paper to safeguard both the interior and exterior. For the outside, use bubble wrap to protect the hardware and shells. This method ensures your drum set remains secure during transit. Drum Packing Tips.