Facilities that ask how to prevent injuries when handling drums must control both mechanical and chemical risks. This article explains typical injury modes, chemical exposure routes, load stability issues, and how regulations shaped modern drum safety practice across industries.

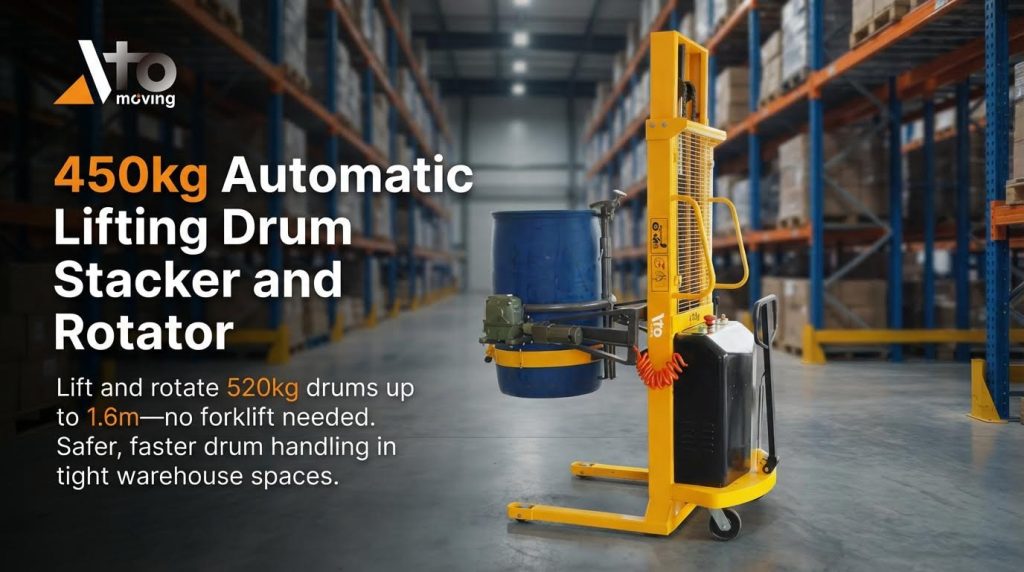

You will see how engineering controls, dedicated drum handling equipment, and automated systems like hydraulic drum stacker reduce manual strain and crush hazards. The article then links safe work procedures, operator training, PPE, and layout rules such as stacking limits and inspection aisles into one integrated control strategy.

Understanding Drum Handling Risks And Hazards

Facilities that ask how to prevent injuries when handling drums need a clear view of risk. Drum tasks combine high loads, possible chemical exposure, and awkward postures. This section explains typical injury modes, containment failures, load behavior, and the standards that guide safe practice. It gives engineers and safety teams a shared basis before selecting equipment or writing procedures.

Typical Injury Modes In Drum Handling Tasks

Most injuries in drum work come from predictable patterns. Common problems include acute back strains, crushed toes and fingers, and impact injuries when drums tip or roll. A full 200 litre steel drum can weigh several hundred kilograms, so even small slips create large forces. Poor posture, twisting lifts, and manual upending increase spinal load and fatigue.

Other injury modes link to handling methods. Uncontrolled rolling can trap feet or strike legs. Unsecured drums on forklifts or pallet trucks can fall during sudden stops or turns. Damaged pallets or sharp edges can puncture drums and cause leaks. To cut these risks, sites should:

- Limit manual lifting and upending of full drums.

- Use purpose-built drum trucks, carts, and attachments.

- Keep floors clean, level, and free of loose material.

- Inspect pallets and storage fixtures before loading.

Clear task planning and route checks also reduce collision and trip hazards during moves.

Chemical Exposure And Containment Failures

Chemical exposure injuries often start with small containment failures. Leaks at bungs, dents at chimes, or punctures from poor pallets can release corrosive or flammable liquids. Contact can cause burns, respiratory issues, or eye damage. Vapors from volatile contents can also create fire and explosion risks.

Controls should follow a simple sequence. First, identify the contents from the label and Safety Data Sheet. If labels are missing, treat the drum as hazardous until confirmed. Second, inspect each drum before movement and secure any loose bungs or lids. Third, define spill response steps and train workers in compatible absorbents and tools.

Good practice also includes:

- Separating incompatible chemicals in storage layouts.

- Using spark-resistant tools where flammable liquids are stored.

- Keeping rows to two drums high and two wide for easy leak checks.

These measures reduce both immediate exposure and secondary incidents such as fires.

Load Characteristics: Weight, Stability, And COG

Understanding drum load behavior is central to how to prevent injuries when handling drums. A typical 55 gallon drum can weigh roughly 180–360 kilograms when full. This weight is concentrated in a tall, narrow cylinder with a high center of gravity. Small tilts can create strong overturning moments, especially on uneven floors or damaged pallets.

Several factors affect stability:

| Factor | Effect on risk |

|---|---|

| Fill level | Partially filled drums can slosh and shift the center of gravity. |

| Drum type | Steel, plastic, and fiber drums have different stiffness and impact behavior. |

| Pallet quality | Warped or broken boards increase rocking and puncture risk. |

| Stack height | Stacks above two high raise the combined center of gravity. |

Operators should estimate drum weight before any move and choose mechanical aids when loads approach handling limits. Stacking should respect manufacturer guidance and internal standards, typically not more than two high in free-standing rows. Stable support surfaces and correct chime contact reduce the chance of progressive collapse.

Regulatory And Standards Context For Drum Safety

Drum safety does not rely on local rules alone. It links to wider regulations on manual handling, hazardous substances, and storage. These frameworks require employers to assess handling tasks, reduce manual lifting where possible, and control exposure to chemicals. They also expect safe stacking, clear aisles, and secure transport of heavy containers.

Key themes across regulations and guidance include:

- Use mechanical aids to avoid high manual loads.

- Train workers in drum-specific rolling, tilting, and upending methods.

- Keep container rows low enough for visual inspection without ladders.

- Maintain floors and walkways in good condition with no obstructions.

Standards and best practice documents also stress labeling, SDS access, and compatibility checks for stored materials. Aligning site rules with these requirements helps reduce injuries, supports enforcement by supervisors, and creates a defensible safety case during audits or incident reviews.

Engineering Controls And Equipment For Safe Handling

Engineering controls are central to how to prevent injuries when handling drums. Well chosen equipment removes most high-risk manual tasks. This section explains how to match drum handling tools to load, route, and process needs. It links design choices to reduced back strain, crush injuries, and chemical exposure.

Selecting Drum Trucks, Carts, And Forklift Attachments

Selection starts with drum size, mass, and content. A full 200 litre drum often weighs 180–360 kilograms. That weight makes manual lifting unacceptable. Drum trucks and carts should keep the drum near the operator’s center of gravity and support it at both chimes. Wide wheels reduce floor point loads and roll better on damaged surfaces.

Forklift attachments are essential when drums move over longer distances or uneven yards. Key points when selecting attachments include: capacity rating above the heaviest filled drum, positive mechanical restraint to prevent slip during sudden stops, and compatibility with fork spacing and mast tilt. Side-clamp or over-the-top grab styles reduce the chance of the drum sliding off.

To support how to prevent injuries when handling drums, choose equipment that allows the operator to stay upright, avoid hand placement under drums, and keep toes clear. Facilities should standardize a small set of truck and attachment types to simplify training and inspection.

Design Criteria For Drum Grabs, Clamps, And Lifters

Grabs, clamps, and lifters must resist both static and dynamic loads. Engineers size these devices with safety factors suitable for lifting equipment, typically at least 4:1 on working load. Jaw or hook geometry must match drum chimes and shell diameters to avoid local crushing or slip. Surfaces that contact the drum should spread load over enough area to keep local stress below shell yield.

Important design criteria include: secure locking that cannot open under vibration, clear visual status of locked or unlocked, and minimal pinch points near operator hands. Where chemical exposure is possible, corrosion resistant materials such as stainless steel or coated carbon steel extend life and maintain clamp function.

Balanced lifting points keep the combined center of gravity under the hook. This reduces swing and lowers the risk of impact injuries. Good clamp design directly supports how to prevent injuries when handling drums by keeping the operator outside the fall zone and away from the load path.

Using Hoists, Manipulators, And Tilt Devices

Hoists and manipulators remove vertical lifting effort and allow precise placement. Electric or pneumatic hoists with drum-specific spreaders can raise drums from pallets, sumps, or bunds without manual strain. Manipulators add controlled rotation and translation, which is useful when feeding reactors, mixers, or filling stations.

Tilt devices allow operators to decant or dose from drums without uncontrolled pouring. Typical systems support controlled rotation from vertical to horizontal and back. Mechanical stops and damped movement avoid sudden shifts in center of gravity that could topple the drum or the support frame.

When choosing these systems, engineers should review: rated load, duty cycle, lifting speed, and control type. Pendant or two-hand controls keep operators clear of the drum during motion. Integrated tilt and lift systems strongly support how to prevent injuries when handling drums because they keep the load within safe height bands between knee and chest level.

Integrating Atomoving And Other AGV/AMR Solutions

Automated guided vehicles and autonomous mobile robots reduce manual pushing and pulling of heavy drum loads. Integration starts with a clear material flow map. Engineers define pick-up points, drop zones, and transfer stations so forklift drum grabber AGVs or AMRs move drums without crossing pedestrian paths where possible.

Drum payload modules on these vehicles should include: cradles or pockets that block rolling, guides that self-center pallets, and sensors that confirm load presence. Speed limits and smooth acceleration profiles reduce dynamic forces on drums and prevent tip events at corners or ramps.

When combining Atomoving systems with other AGVs or AMRs, designers must align communication and traffic control rules. Geofenced zones, right-of-way logic, and obstacle detection cut collision risk. This automation strategy supports how to prevent injuries when handling drums by taking workers out of repetitive transport tasks and away from forklift traffic, while still keeping manual override and emergency stop options for supervisors.

Safe Procedures, Training, And Workplace Layout

This section explains how to prevent injuries when handling drums through procedures, skills, PPE, and layout. It links risk assessment with daily practices so supervisors can turn safety rules into repeatable routines. The focus stays on typical 200 litre steel or plastic drums, but the principles apply to other heavy containers.

Pre-Handling Checks, Labeling, And SDS Review

Pre-handling checks form the first control layer when planning how to prevent injuries when handling drums. Operators should confirm three points before touching any drum: what is inside, what condition the container is in, and how heavy it is. Labels and placards must show product name, hazard class, and key warnings; if a drum is unlabeled, treat it as hazardous until identified.

Before moving a drum, workers should:

- Visually inspect for leaks, bulging, corrosion, or damaged chimes.

- Check bungs and lids and tighten or replace missing closures.

- Estimate mass from fill level and product density; a 200 litre drum often weighs 180–360 kg.

Supervisors should require quick SDS review for new or infrequent products. The SDS gives limits for skin contact, inhalation, and reactivity, and it lists correct absorbents and neutralisers for spills. A simple checklist at drum staging areas helps standardise these steps and reduces skipped checks during busy shifts.

Manual Techniques For Rolling, Upending, And Positioning

Even with equipment, workers still roll and upend drums in tight spaces. Poor technique drives back injuries and crushed fingers, so methods must be clear and consistent. For rolling, the operator should stand in front of the drum, place both hands on the far side of the top chime, pull until the drum balances on the lower chime, then walk it forward. Hands must never cross, and feet must never act as stops.

For lowering a vertical drum to rolling position, workers should shift hands to the upper half of the chime, keep the back straight, bend at the knees, and control the descent. To upend a drum, a drum stacker is preferred because it keeps the spine neutral and hands clear of pinch points. If manual upending is unavoidable, the worker should crouch with knees apart, grip the chime on both sides, keep the back straight, and lift with leg muscles only. Training sessions should use empty or water-filled drums first, then progress to real loads under supervision.

PPE Selection For Mechanical And Chemical Hazards

PPE should match both the mechanical risks and the chemical profile of the drum contents. Foot protection is non-negotiable; safety shoes with toe caps and slip-resistant soles reduce crush and slip injuries during drum moves. Impact-resistant gloves protect fingers from pinches and sharp edges, while chemical-resistant gloves are needed when corrosive or toxic products are present.

Eye and face protection should reflect splash risk. For sealed inert products, safety glasses are often enough. For corrosive or volatile liquids, use chemical goggles plus a face shield, especially during venting, sampling, or connecting hoses. Aprons or chemical suits protect the torso when splash potential is high or when workers open suspect drums. Supervisors should document PPE by product group in a simple matrix, linking each drum label or hazard class to minimum PPE, so operators do not guess at protection level.

Layout, Stacking Limits, And Inspection Access

Workplace layout strongly affects how to prevent injuries when handling drums. Good layout shortens push distances, reduces twisting, and keeps heavy drums within equipment reach. Aisles should be wide enough for trucks to turn without side loading pallets, and floor conditions must stay dry and even to prevent slips during rolling or steering.

Stacking rules must be clear and enforced. A common safe practice stored 200 litre drums in rows no more than two high and two wide. This limit allowed visual inspection of bungs, seams, and labels without ladders and reduced risk from variable drum strength and pallet quality. Pallets should be flat, undamaged, and free of protruding nails or splinters that could puncture bases.

Inspection access is as important as stack stability. Rows that hide inner drums force extra handling just to see conditions, which increases manual contact and equipment moves. Marked inspection aisles, defined stacking zones, and posted height limits help operators make correct decisions in real time. Regular walk-throughs by supervisors can verify that layout rules and manual handling techniques match written procedures.

Summary: Key Controls To Prevent Drum Injuries

Facilities that ask how to prevent injuries when handling drums need a simple control framework. The most effective approach combined four elements. These were hazard recognition, engineered handling aids, disciplined procedures, and safe layouts. When aligned, these controls cut both musculoskeletal and chemical risks.

From a technical view, the main injury drivers were drum mass, unstable loads, and unknown contents. Controls started with reading labels, checking SDS, and treating unlabeled drums as hazardous. Pre-use inspection for leaks, damage, and missing bungs reduced exposure events. Weight estimates and centre-of-gravity checks helped decide when to use equipment or team lifts.

Engineering controls stayed at the core of modern drum safety. Sites used drum carts, forklift drum grabber, hoists, and manipulators to avoid manual lifting. Operators followed standard methods for rolling, upending, and lowering drums to keep loads close and backs neutral. PPE closed the gap for residual mechanical and chemical hazards.

Layout and storage rules supported these measures. Typical guidance limited rows to two drums high and two drums wide for inspection access. Clear aisles, sound pallets, and clean floors reduced impact, trip, and puncture risks. Future systems increasingly linked AGVs, sensors, and digital checklists, but still relied on basic principles: know the contents, control the load, use the right tool, and keep stacks inspectable.