A drum used to transport crude oil sits in a much wider system that includes large storage tanks, pipelines, and rail or road tankers. This article links small‑volume packaging, like 200 litre drums, with the broader engineering and regulatory framework that governs crude, dilbit, and condensate logistics.

You will see how drum and barrel standards define volumes, materials, and fill limits for hazardous liquids, and how engineering specs control pressure, temperature, venting, stacking, and palletization. Later sections explain safe handling and transport of oil drums, from ergonomic risks to cargo securing, inspection, and grounding. The summary section then distills key design and selection points so engineers can choose and operate crude oil drums that align with tank standards such as API 650, API 620, and EN 14015, and with modern safety expectations across terminals, depots, and refineries.

Drum And Barrel Standards For Crude Oil

Engineers who specify a drum used to transport crude oil must align container geometry, materials, and codes. This section explains how standardized barrel volumes, drum sizes, and fill limits support safe storage and transport. It then compares material options, regulatory definitions, and fluid compatibility for crude, dilbit, and condensate. The goal is a clear design basis for compliant, durable crude oil drum systems.

Barrel Volumes, Drum Sizes, And Fill Limits

The commercial crude oil unit is the barrel, defined as 42 US gallons, or about 159 litres. In contrast, a standard steel drum used to transport crude oil typically has a nominal volume of about 208 litres, often called 55 US gallons. This mismatch means one drum does not equal one crude oil barrel, which matters for custody transfer, inventory, and logistics planning.

Engineers size drum fill levels by volume and expansion headspace. Flammable liquids must not be filled to 100% of geometric volume because thermal expansion can create overpressure. Typical practice is to leave a vapour space, often 3% to 5% of drum capacity, depending on product vapour pressure and expected temperature range. Regulations and standards for dangerous goods transport require that filled drums pass leakproofness and drop tests at the specified fill level.

For warehouse and vehicle loading, weight also limits filling. A 55-gallon drum of crude or heavy product can reach 180 kilograms to 360 kilograms, depending on density. Designers must check that filled drum mass remains within manual handling rules, pallet ratings, and vehicle axle load limits.

Material Options And Corrosion Resistance

A drum used to transport crude oil usually uses carbon steel because it offers high strength and reasonable cost. However, crude oil is not a single fluid. It can contain water, hydrogen sulphide, salts, and organic acids. These components drive corrosion, especially under storage or when drums sit outdoors.

Material selection balances several factors:

- Carbon steel: Good strength and impact resistance. Needs coatings or linings for corrosive crudes.

- Stainless steel: Better resistance to chlorides and acids. Higher cost, used for aggressive blends or high-value products.

- Internal linings: Epoxy or phenolic linings reduce under-film corrosion and contamination risk.

Engineers also consider external corrosion. Outdoor storage exposes drums to rainwater and marine atmospheres. Paint systems, sacrificial coatings, and raised pallets limit standing water and extend drum life. For long-term crude storage, large welded tanks designed to API 650 or similar standards often replace drums. These tanks use pressure and temperature limits, corrosion allowances, and inspection regimes that differ from small portable drums but follow the same durability goals.

Regulatory Definitions And Classification Codes

Regulations define how a drum used to transport crude oil must be built, tested, and marked. Dangerous goods rules classify crude oil as a flammable liquid with a UN number and packing group, based on flash point and boiling range. These rules apply to road, rail, and sea transport and drive design choices for drums and closures.

Key regulatory elements include:

- UN packaging codes for steel drums, which specify performance tests such as drop, leakproofness, and hydraulic pressure.

- Markings that show drum type, material, performance level, and year of manufacture.

- Compatibility rules that require the drum material and lining to resist attack from the specific crude, dilbit, or condensate.

Large fixed tanks for crude storage follow different standards such as API 650, API 620, or EN 14015. These standards define design pressure, design temperature, materials, and inspection requirements. While these codes target tanks above roughly 100 cubic metres, the same principles of leak prevention, venting, and structural integrity guide small drum design and selection.

Compatibility With Crude, Dilbit, And Condensate

Crude oil, diluted bitumen, and condensate have different densities, viscosities, and vapour pressures. These differences affect how a drum used to transport crude oil behaves in service. Heavier crude and bitumen blends place higher static loads on drum walls and bottoms. Light condensate generates higher vapour pressure and more flammable atmospheres inside the headspace.

Compatibility assessment covers three areas. First, chemical compatibility between fluid and drum material or lining. Acidic or sour crudes may require upgraded steels or internal coatings to avoid pitting and sulphide stress cracking. Second, mechanical loads from density and handling. Dense dilbit increases drop-test severity and stacking loads. Third, thermal and pressure effects. Condensate can expand strongly with temperature, so engineers must set conservative fill limits and ensure reliable pressure relief at the system level.

Blends such as dilbit also change logistics. Pipeline transport often needs condensate addition to meet viscosity targets, while rail can move undiluted bitumen at elevated temperatures. When these products move in drums, operators must confirm that blend composition matches the tested configuration for that drum type. This alignment keeps performance within certified limits and supports safe, compliant crude oil drum transport.

Engineering Specs For Crude Oil Storage Drums

Engineering specs for a drum used to transport crude oil must control pressure, temperature, and mechanical loads. Designers also balance sealing, corrosion, and stacking strength against regulatory limits. The goal is predictable behavior from filling, through transport, to long-term storage. This section focuses on how design pressure, structure, and sealing work together in crude oil drum systems.

Design Pressures, Temperatures, And Venting

A drum used to transport crude oil operates near atmospheric pressure but must tolerate internal pressure spikes. Vapor growth, solar heating, and sloshing can raise internal pressure well above normal conditions. Typical design practice uses a safety margin above expected vapor pressure at the highest service temperature.

For crude, dilbit, and condensate service, engineers set a design temperature envelope that covers likely climates. This usually spans sub-zero ambient conditions up to hot yard or deck exposure. Steel drums maintain strength over this range, but gaskets and sealants must also stay flexible and tight.

Venting strategy is critical. Normal venting handles slow vapor build-up during filling and heating. Emergency venting protects the shell from rupture during fire exposure or blocked vent events. For drums, this function comes from controlled leak paths at closures and from head distortion before catastrophic failure.

Key design checks for pressure and temperature include:

- Maximum vapor pressure of the crude blend at peak temperature

- Allowable drum deformation without loss of closure integrity

- Compatibility of gaskets and linings with expected temperature swings

- Static charge control during venting and filling

Structural Integrity, Stacking, And Palletization

Structural integrity for a drum used to transport crude oil depends on shell thickness, chime design, and head profile. The drum must resist local dents from handling and global buckling from stacking. Engineers size the shell to carry axial compression from upper drums and bending from impacts.

Stacking rules for oil drums limit tiers to maintain stability and allow inspection. A common practice keeps palletized 200 litre drums to two high in warehouses. This limit reflects variability in drum condition, pallet stiffness, and floor flatness. Higher stacks increase risk of progressive collapse if a lower drum fails.

Palletization spreads loads and simplifies forklift handling. A standard pattern places two or four drums on a pallet, with drum chimes aligned. Good practice keeps no overhang and uses pallets with known load ratings. The combined mass of drums and pallet must remain within floor and rack limits.

When engineers specify stacking, they consider:

| Aspect | Design focus |

|---|---|

| Drum shell thickness | Compression from upper tiers and impact resistance |

| Chime geometry | Load transfer between drums in a stack |

| Pallet stiffness | Limiting differential settlement and tilt |

| Warehouse floor rating | Point loads from stacked pallets |

Sealing Systems, Bungs, Linings, And Gaskets

Sealing systems keep volatile crude and vapors inside the drum and keep water and dirt out. A drum used to transport crude oil normally uses tight-head construction with threaded bungs. Typical layouts use one larger filling bung and one smaller vent bung. Both must withstand repeated opening cycles without loss of seal quality.

Gasket materials must match the crude type. Light sweet crude, condensate, and dilbit each contain different aromatics, sulfur levels, and additives. These can attack some elastomers and plastics. Engineers select gasket compounds tested for swelling, softening, and permeation under expected temperature and storage time.

Internal linings protect the steel from corrosion and protect the product from contamination. Unlined carbon steel suits many crude grades. However, more aggressive blends or long storage times can justify epoxy or phenolic linings. The lining must resist softening in contact with hydrocarbons and survive drum forming and welding temperatures.

Key sealing design points include:

- Thread form and surface finish at bungs and plugs

- Torque range that achieves tightness without thread damage

- Compatibility of linings with both crude and cleaning agents

- Ease of visual inspection for gasket seating and coating defects

Well-engineered closures reduce leak risk during loading, road or sea transport, and long-term yard storage. They also support safe venting and grounding practices during filling and emptying.

Safe Handling And Transport Of Oil Drums

Safe handling of a drum used to transport crude oil depends on strict ergonomic, mechanical, and electrostatic controls. Operations teams must control manual handling forces, drum stability, vapor ignition sources, and tie-down loads during road, rail, or sea transport. This section links field practice with regulatory expectations for flammable liquids in closed containers.

Manual Handling Risks And Ergonomic Controls

A drum used to transport crude oil can weigh 180 kilograms or more when full. Manual pushing, pulling, or tilting creates high spinal compression and shear loads. Poor technique or rushed work often leads to back strains, crushed fingers, or foot injuries.

Engineering controls should reduce direct lifting and long-distance rolling. Typical controls include:

- Use trolleys, pallet jacks, or drum trucks for any move over a few metres.

- Limit manual tilting to short repositioning tasks on flat, dry floors.

- Set clear limits for maximum push and pull forces per person.

- Provide non-slip footwear and impact-resistant safety shoes.

Supervisors should standardize handling methods for steel and composite drums. Training must cover chime rolling, two-person tilting, and safe work around inclined ramps. Clear walkways and good lighting reduce trip risks when operators guide drums.

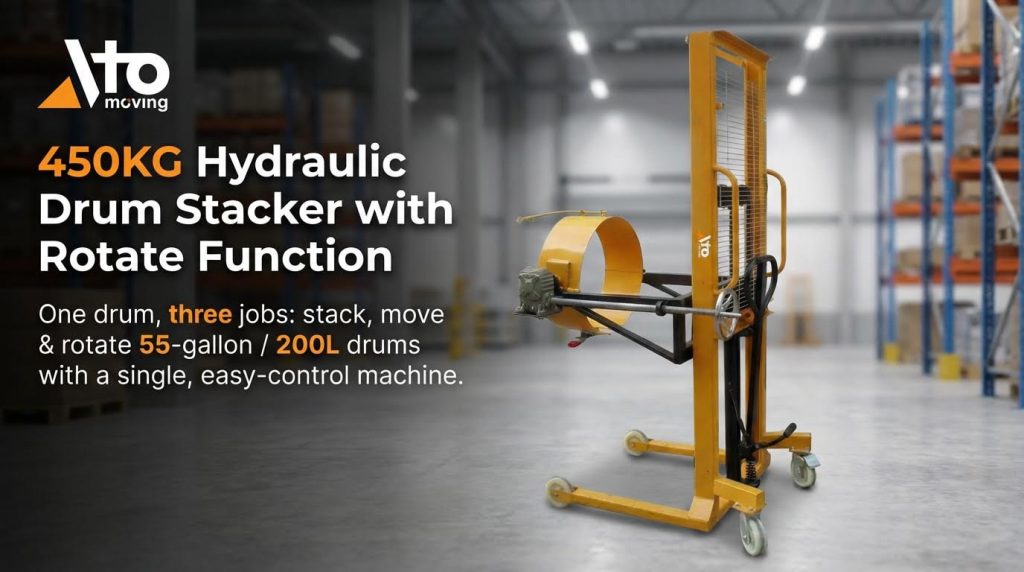

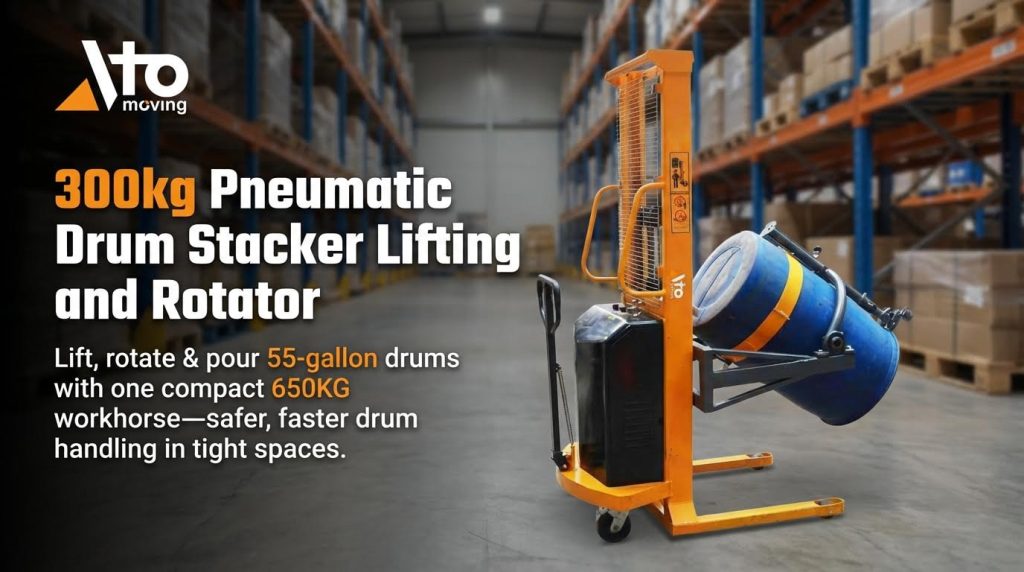

Drum Handling Equipment And Automation Options

Mechanical aids are essential when a drum used to transport crude oil moves through filling, staging, and loading stations. Equipment selection must match drum type, floor condition, and transfer rate. Over-specified systems add cost, while under-specified tools raise incident rates.

Common equipment options include simple and automated solutions:

| Equipment type | Main use | Key benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Drum trucks and dollies | Short moves on smooth floors | Reduce manual lifting |

| Pallet jacks and forklifts | Palletized drum transport | High throughput |

| Hydraulic drum lifters | Vertical lifting and stacking | Controlled elevation |

| Conveyors or roller beds | Fixed transfer lines | Low manual effort |

Automation, such as powered drum turners or robotic palletizers, suits high-volume terminals. These systems improve repeatability and reduce human contact with crude-contaminated surfaces. Where budgets are tight, facilities can still gain safety by standardizing simple carts and properly rated slings.

Loading, Securing, And Transferring Drum Cargo

Transport planners must treat each drum used to transport crude oil as a rigid dangerous-goods package. Load plans should keep the centre of gravity low and evenly distributed. Mixed loads with lighter goods above drums increase crush and shift risk under braking.

Key loading and securing practices include:

- Place drums upright on sound pallets or dunnage with full deck boards.

- Interlock rows where possible to limit lateral movement.

- Use blocking, bracing, and straps rated for expected deceleration loads.

- Check that trailer or container floors can support point loads at pallet corners.

Transfer from storage to vehicle should follow a defined path with no sharp slopes. Ramps must have cleats or high-friction surfaces to prevent rollaway. During loading and unloading, operators should avoid standing downslope of free-rolling drums. For rail or sea transport, lashings must consider vibration, sway, and long-duration fatigue on tie-down hardware.

Inspection, Leak Control, And Grounding Practices

Every drum used to transport crude oil should pass a visual inspection before movement. Checks must confirm tight bungs, undamaged chimes, and no bulging or severe corrosion. Any drum with suspected deformation should move to a controlled rework or salvage area.

Leak control starts with early detection and fast containment. Typical measures include drip trays at loading points, absorbent pads near transfer hoses, and labeled salvage overpacks for compromised drums. Secondary containment around staging areas should hold at least the volume of the largest drum plus a margin set by local rules.

Grounding and bonding are critical when handling flammable crude or condensate. Operators must bond drum, transfer hose, and receiving vessel before opening any closure. Grounding clamps should bite into bare metal, not painted or oily surfaces. Facilities should verify continuity of bonding cables on a routine schedule. Clear procedures for spill response, fire isolation, and decontamination complete the safety envelope for drum-based crude transport.

Summary And Key Design Considerations

A drum used to transport crude oil works as a small, mobile pressure envelope. It links field production, terminals, and refineries where large atmospheric tanks follow API 650, API 620, or EN 14015. Design choices for drums must align with these wider storage and transport systems so fluids stay compatible, stable, and traceable across the chain.

For a drum used to transport crude oil, engineers must balance four factors. First, mechanical strength under static stacking and dynamic handling. Second, chemical resistance to crude, dilbit, and condensate. Third, sealing and venting that control vapor, pressure, and leaks. Fourth, regulatory fit with packing groups, UN markings, and modal rules. Typical 200 litre steel drums operate near atmospheric pressure but still see local impact loads, temperature swings, and internal pressure pulses during heating and transport.

Key design considerations include drum shell thickness, chime geometry, and pallet interface. These details govern stacking limits and floor loads. Linings, gasket materials, and bung design must match fluid type, water content, and any required heating cycles. Grounding points, bonding practice, and clear marking reduce ignition and handling risk. Compared with large fixed tanks, drums see higher handling cycles and more variable operators, so conservative safety factors and clear procedures matter.

Future practice will link a drum used to transport crude oil with more sensors, digital tracking, and automated handling. However, robust shells, proven closures, and disciplined inspection will stay central. Operators that align drum specification, storage layout,,

Frequently Asked Questions

What is an oil drum?

An oil drum is a cylindrical container used for storing and transporting oils and greases. It typically holds 55 gallons of oil or about 410 pounds of grease. These drums are often accessed through a drum cover. Oil Drum Glossary.

What is the difference between an oil barrel and an oil drum?

An oil barrel, as a unit of measurement, equals 42 U.S. gallons, while actual drums used in the industry can hold 55 U.S. gallons. This distinction is important when discussing quantities in the oil industry. Oil Measurement Details.