Facilities searching for how to stack oil drums safely must balance storage density, spill control, and strict fire code rules. This article explains how OSHA 1910.106, NFPA 30, and related standards shape compliant layouts for flammable and combustible liquid drums in warehouses and yards.

You will see how drum types, fill levels, closure torque, and specific gravity limit safe stack heights and pallet patterns on concrete floors and racking systems. The article then links stacking practice with secondary containment sizing, sump pallets, diked areas, ventilation, ignition control, and outdoor weather protection for oil drums.

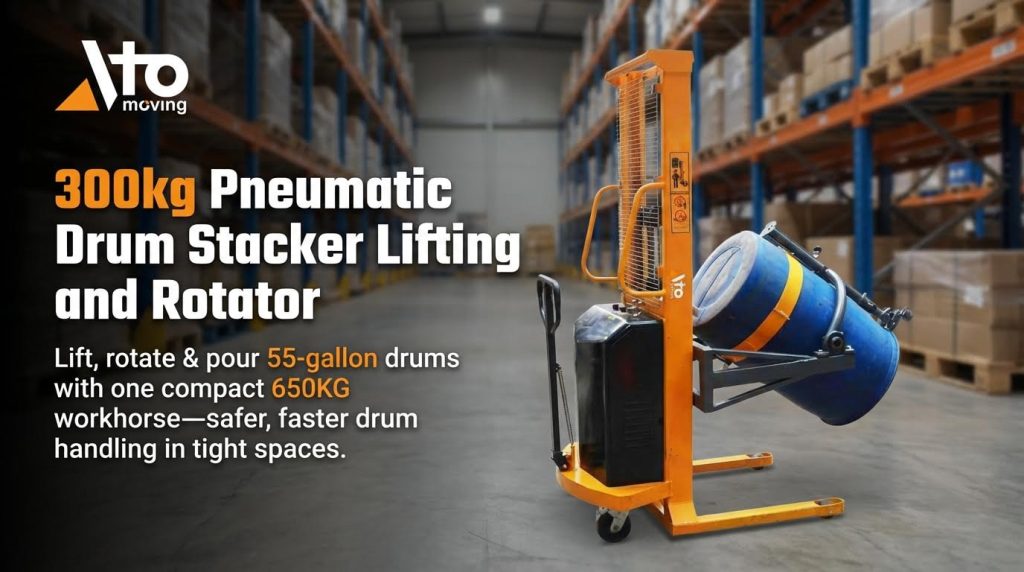

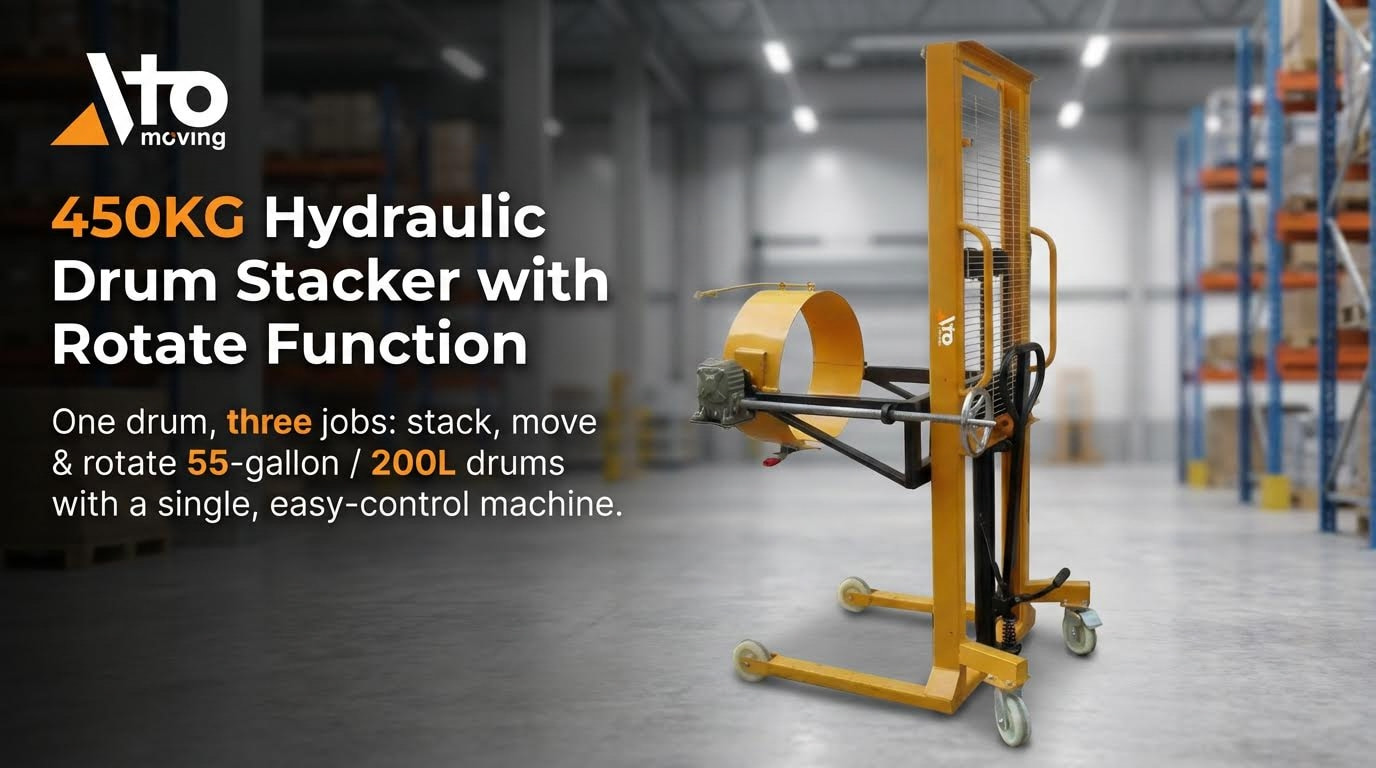

The final section shows how to integrate safety, regulatory compliance, and lifecycle cost when designing or upgrading oil drum storage systems. Engineers, EHS leaders, and operations teams can use these rules to build defensible standards for drum stacking, handling equipment such as hydraulic drum stacker, drum stacker, and electric drum stacker, and long term risk reduction.

Regulatory Framework For Oil Drum Storage

Facilities that search for how to stack oil drums safely must first understand the regulatory context. OSHA 1910.106 and NFPA 30 set the baseline rules for flammable and combustible liquid storage. These codes define container types, volume limits, fire protection, and separation distances. Correct stacking is only compliant when it fits inside these broader storage rules.

OSHA 1910.106 And NFPA 30 Scope And Definitions

OSHA 1910.106 governed the storage, handling, and use of flammable and combustible liquids in workplaces. It covered approved containers, portable tanks, and indoor and outdoor storage areas. NFPA 30 provided the technical fire code behind many OSHA requirements. It defined design rules for storage rooms, cabinets, and tank systems.

For engineers planning how to stack oil drums, these definitions mattered. They decided when a drum was a “container” versus a “portable tank,” and what fire protection applied. They also linked to requirements for pressure-relieving fittings, emergency venting, and sprinkler protection over drum stacks. Any stacking layout had to be checked against these scope limits.

Combustible Liquid Classes And Flash Point Limits

Oil drums usually held combustible liquids rather than highly flammable liquids. NFPA 30 and OSHA classified liquids by flash point and boiling point. Typical engine and hydraulic oils fell into higher flash point classes. Some standards placed oils above 93 °C flash point in a combustible class similar to C2.

These classes drove storage rules that impact how to stack oil drums:

- Maximum drum counts per area

- Need for fire-rated rooms or cabinets

- Sprinkler density and foam-water system design

Lower flash point liquids triggered stricter stacking and spacing limits. Higher flash point oils allowed larger quantities but still needed containment and separation from ignition sources. Engineers had to confirm the exact product class before setting stack heights or rack layouts.

Indoor Vs. Outdoor Storage Quantity Thresholds

Codes set different volume limits for indoor and outdoor storage. Indoors, only small amounts of flammable and combustible liquids could stay outside approved cabinets or rooms. Typical rules limited cabinet quantities by class and capped the number of cabinets per fire area. Larger indoor volumes required dedicated storage rooms designed per NFPA 30.

Outdoors, total group capacity and distance rules applied. Groups of drums had maximum aggregate volumes and minimum separations from buildings, combustibles, and other groups. Access ways at least about 3.6 metres wide supported firefighting. When deciding how to stack oil drums, designers had to check whether the stack raised the group capacity above a threshold that changed these distances or required diking.

Penalties And Liability For Non‑Compliance

Non-compliant drum storage exposed operators to significant penalties and liability. OSHA could cite each serious or other-than-serious violation with fines above USD 16,000 per item. Willful or repeated violations could exceed USD 160,000 per case. Failure to fix hazards after the due date added daily penalties.

Beyond fines, poor decisions about how to stack oil drums increased fire and spill risk. A collapse or fire could trigger environmental cleanup costs, business interruption, and civil claims. Regulators and insurers often reviewed whether stacking followed OSHA 1910.106, NFPA 30, and spill control rules. Documented engineering calculations, inspections, and operator training helped show due diligence and reduced liability when incidents occurred.

Engineering Rules For Safe Drum Stacking

Engineering rules for how to stack oil drums focus on container integrity, floor loading, and fire protection. Designers must link drum type, fill level, and closure torque to realistic stack heights and rack layouts. This section explains how specific gravity, pallet design, and venting hardware work together to keep stacks stable and compliant. The goal is repeatable layouts that pass inspection and survive real fire and impact events.

Drum Types, Fill Levels, And Closure Torque Requirements

Engineers should first match stacking rules to drum construction. Common oil drums include tight-head steel drums, open-head steel drums, and plastic drums. Tight-head steel drums with welded seams usually support higher stacks than plastic drums with molded ribs. Open-head drums with removable lids often have lower stacking ratings due to ring flexibility.

Fill level affects internal pressure and impact resistance. Filled drums resist denting better but can over-pressurize under heat. Partially filled drums can deform under stacked loads because liquid sloshing shifts the center of gravity. Store engine oils and other C2 combustible liquids away from direct sunlight or hot surfaces to limit thermal expansion.

Closure torque is critical when you plan how to stack oil drums vertically. Title 49 CFR §178.2(c) required closures be tightened to the torque specified by the manufacturer. Under-torqued bungs can leak under stack load or during heating. Over-torqued bungs can damage gaskets and reduce fire performance. Facilities should use calibrated torque wrenches and keep torque records for audit trails.

| Drum type | Typical behavior in stacks |

|---|---|

| Tight-head steel | Highest axial strength; suitable for three to four-high stacks within rating. |

| Open-head steel | Lower ring stiffness; check manufacturer limits before three-high stacking. |

| Plastic drum | More sensitive to temperature and creep; often limited to two or three-high. |

Maximum Stack Heights, Specific Gravity, And Stability

Maximum stack height depends on drum rating, liquid specific gravity, and base conditions. Published guidance indicated steel drums with liquids of specific gravity up to 1.5 could be stacked four-high. For higher specific gravity, stacks should be limited to three-high to keep shell stresses and chime loads within design limits. Oils usually have specific gravity below 1.0, so drum design often governs rather than weight alone.

When planning how to stack oil drums, treat stability as a separate design check. Evaluate:

- Height-to-base ratio of the stack.

- Potential impact from manual pallet jack or pallet jacks.

- Seismic or wind loads for outdoor yards.

Palletized stacks should not exceed around 3.0–4.0 times their narrowest base dimension in height without restraint. Codes and industry guidance also set absolute limits. One reference limited palletized drum stacks to about 3.0 metres for three-high and about 4.2 metres for four-high. Keep rows straight and avoid mixed drum sizes inside one stack.

Use chocks, rack beams, or side guides where impact risk is high. Inspect stacks routinely for leaning, drum denting, or pallet damage. Any visible tilt or crushed ring is a reason to reduce height or restack.

Pallet Design, Floor Conditions, And Racking Systems

Pallet design strongly affects how to stack oil drums safely. Drums need full chime support, not just point contact. Recommended pallet sizes were about 1 220 millimetres by 1 220 millimetres or at least 1 170 millimetres square. Pallets must be sound, with intact deck boards and stringers. Avoid broken or heavily warped pallets, which create line loads on drum chimes and trigger shell buckling.

If drums sit directly on the floor, the surface should be flat, smooth, and oil-resistant. Concrete floors with sealed surfaces work best. Rough or sloped floors increase rocking and sliding risk. Check floor load capacity against worst-case stacks, including pallet weight and secondary containment hardware.

Selective pallet racking suits drum storage because it gives direct access and clear load paths. Two main rack methods existed:

- Vertical storage of palletized drums on beams.

- Horizontal storage of single drums cradled on two beams.

For vertical pallet storage, ensure beam capacity and deflection limits match the mass of a full pallet of drums. For horizontal storage, each drum must rest on two beams or cradle saddles to prevent point loading. Drums must be fixed with hooks, cradles, or restraints so they cannot roll out under vibration or impact. Racks should include back stops where aisles run behind stacks.

Integrate spill pallets or sump decks under rack bays where regulations require secondary containment. Confirm that sump systems can carry the combined weight of racks, pallets, and drums without excessive deflection.

Venting, Pressure Relief, And Fire Protection Systems

Venting and pressure relief hardware protect stacked drums during fire exposure. NFPA 30 required pressure-relieving fittings for drums that store flammable or combustible liquids. Guidance specified relieving-style plugs in the 50.8 millimetre and 19.05 millimetre openings on steel drums when stacked. These plugs allowed controlled venting in a fire and reduced drum rupture risk.

When deciding how to stack oil drums under sprinklers, coordinate stack height with fire protection design. One standard foam-water system used discharge densities of about 18.3 litres per minute per square metre for three-high stacks. For four-high stacks, density increased to about 24.5 litres per minute per square metre. Sprinkler heads were pendant extra-large orifice types to deliver enough foam-water mix through the stack.

Stack layout must preserve sprinkler effectiveness. Maintain required vertical clearance between the top of the stack and sprinkler deflectors. Avoid solid shelving that blocks water travel unless in-rack sprinklers are installed. For indoor storage, keep stacks away from ignition sources such as heaters or hot process lines.

Ventilation systems help remove vapours that may form at elevated temperatures. Even though engine oils have high flash points, vapour build-up in confined rooms can still create odour, slip, or long-term health issues. Combine mechanical exhaust with clear “No Smoking” rules and visible signage. During engineering reviews, verify that venting, fire water supplies, and stack heights align with the worst-case drum inventory and liquid class stored.

Spill Prevention, Containment, And Site Design

Spill control is the foundation of any strategy for how to stack oil drums safely. Good site design limits spill spread, protects drains, and supports code compliance. Engineering choices for secondary containment, drainage, ventilation, and security must all work together. The goal is simple: a spill stays small, contained, and easy to clean.

Secondary Containment Sizing And Configuration

Secondary containment must match the worst credible spill from stacked drums. Regulations in different regions required capacities from about 25% of the largest drum up to 110% of a single container volume. For grouped drums, engineers usually size for either the largest single drum or a defined percentage of the total group, whichever is higher. This logic prevents under-sized bunds when stacks grow over time.

When planning how to stack oil drums, containment geometry matters as much as volume. Common options include:

- Spill pallets under single or small groups of drums.

- Diked concrete bays for larger inventories.

- Modular sump flooring for flexible layouts.

Engineers check freeboard for fire water and rain, wall height for forklift barrel grabber access, and slope toward a low point for pumping. Surfaces should be sealed and oil-resistant to avoid seepage into soil or subgrade.

Sump Pallets, Diked Areas, And Drainage Control

Sump pallets work well for small stacks and frequent drum moves. They capture leaks directly below the drums and allow quick visual checks of liquid level. Load rating, grate design, and chemical compatibility must match drum mass and fluid type. Steel sumps suit oils but not strong acids or alkalis, where polyethylene is safer.

Diked areas serve higher volumes and fixed stack layouts. Good practice uses:

| Design aspect | Typical requirement |

|---|---|

| Wall height | Enough for spill volume plus freeboard |

| Floor finish | Concrete, sealed, oil-resistant |

| Gradient | Fall to a collection sump or drain |

Drainage from bunds must never discharge directly to storm sewers. Sites often use manual valves, oil-water separators, or passive filtration devices. Operators only open drains after visual checks confirm no floating oil. This discipline becomes critical when stacked drums sit outdoors and receive rainwater.

Ignition Source Separation, Ventilation, And Signage

Spill design must assume that vapors or mists can form near stacked drums under fault conditions. Standards for combustible liquids required separation distances from ignition sources, often at least a few metres. Engineers map likely spill paths and then remove or shield hot surfaces, electrical gear, and vehicle charging points in that zone.

Ventilation reduces vapor build-up in indoor drum stores. Designers prefer natural crossflow first and then add mechanical exhaust if modeling shows dead zones. Air changes must suit the liquid class and room volume. Exhaust points should sit near potential vapor layers, often low for heavy hydrocarbons.

Clear signs support both stacking control and fire safety. Typical signs include:

- “No Smoking” and “No Open Flames” at all entries.

- Maximum stack height and pallet count per bay.

- Spill response and emergency contact details.

Floor markings guide walkie pallet truck paths and keep aisles free for emergency access and spill kits.

Outdoor Storage, Weather Protection, And Security

Outdoor sites for stacked oil drums need stronger focus on weather and security. Rainfall increases containment volume demand and can flood sumps if designers ignore local storm data. Snow and ice loads also affect rack stability and roofed structures over drum stacks. Surfaces must stay level and non-slip to prevent drum movement and forklift barrel grabber skids.

Weather protection reduces drum corrosion and thermal stress. Options include canopies, drum covers, or full enclosures with natural ventilation. Keeping filled drums out of direct sun limits thermal expansion and pressure rise. This reduces the risk of weeping closures or activation of pressure-relief fittings.

Security planning assumes that unauthorized access can lead to vandalism, valve tampering, or theft. Typical measures are fences, controlled gates, lighting, and cameras. Access control should match the spill consequence level and regulatory risk. Good practice also includes regular inspections for damage, missing bungs, or tipped drums along fence lines and remote corners.

Summary: Integrating Safety, Compliance, And Lifecycle Cost

Facilities that search for how to stack oil drums safely must link engineering rules with regulatory limits and long term cost. Safe stacking depends on drum design, closure torque, specific gravity, pallet quality, and floor conditions. Codes like OSHA 1910.106 and NFPA 30 set quantity thresholds, containment duties, and fire protection performance. Spill control design then ties storage geometry to dikes, sumps, and drainage paths.

From an engineering view, best practice keeps stacks within tested drum ratings and verified rack or slab capacity. Typical guidance limited steel drums with specific gravity up to 1.5 to four high, and three high above that. Palletized stacks needed controlled total height and clear access for sprinklers, hose streams, and inspection. Secondary containment usually sized from 25% to 110% of vessel volume, depending on jurisdiction and container type.

Lifecycle cost favored layouts that reduced handling cycles, avoided drum damage, and minimized spill cleanup risk. Well designed containment and racking reduced insurance exposure and unplanned downtime. Future trends pointed toward more use of sensors, digital inspection records, and integrated fire detection tied to foam water systems. These tools did not replace fundamentals such as level oil resistant floors, clear aisles, and tight drum closures.

In practice, facilities should document a single standard for how to stack oil drums, including maximum tiers, pallet specifications, and separation distances. That standard should align with fire code, environmental rules, and insurer requirements. Periodic engineering review is essential when storage density, product mix, or equipment changes. A balanced approach treats stacking height as only one variable within a wider system that includes containment, ventilation, ignition control, and secure access. For facilities using specialized equipment, options like the hydraulic drum stacker, drum stacker, and forklift drum grabber can enhance safety and efficiency during drum handling operations.