Facilities that search for how to lift a heavy barrel usually face combined safety, ergonomic, and productivity pressures. This article explains how to design safe lifting operations for drums and barrels using structured risk assessment, compliant procedures, and engineered handling equipment.

You will see how formal lift planning, manual handling limits, and storage rules work together to control hazards from 200–360 kilogram drums and similar containers. The article then compares trucks, drum lifters, cranes, AGVs, and advanced manipulators, including their role with sensors and digital twins. The final section turns these insights into clear selection criteria and best practices for safe, efficient barrel handling across industrial sites.

Risk Assessment For Barrel Lifting Operations

Risk assessment is the first step when deciding how to lift a heavy barrel. It sets clear limits for what is safe, what equipment is needed, and how people should work. A structured assessment also supports legal compliance and protects the site from downtime, damage, and injury claims. The following sections break the process into standards, planning, hazard checks, and control measures that safety teams can apply to any drum, keg, or barrel lift.

Legal And Standards Framework (OSHA, LOLER, ISO 45001)

When planning how to lift a heavy barrel, duty holders must align with core safety laws and standards. In the United States, OSHA rules required employers to identify lifting hazards, maintain equipment, and train operators. In the United Kingdom, LOLER required that every lifting operation be properly planned, supervised, and carried out by competent people. ISO 45001 set a management framework for occupational health and safety, including formal risk assessment for lifting work.

These rules had common themes. Each required documented risk assessment before the lift. Each required safe working loads on lifting gear and proof of inspection. Each demanded that employers control exposure to hazardous substances inside the barrel through labels, Safety Data Sheets, and PPE. For heavy drums, compliance meant written procedures for drum mover, hoists, and attachments, plus clear exclusion zones for people on the ground.

| Aspect | Requirement focus |

|---|---|

| Planning | Documented lift plan and risk assessment |

| Equipment | Rated capacity, inspection, and maintenance |

| People | Competent operators and clear roles |

| Environment | Safe access, egress, and ground conditions |

Step-By-Step Lift Planning And Risk Matrix Use

A step-by-step lift plan turns the legal duty into practical actions. The plan should be short, clear, and task specific. For heavy barrels, planners usually follow a simple sequence.

- Define the task. Describe the barrel type, weight range, contents, and travel path.

- Select the method. Decide if the lift is manual assist, mechanical, or fully powered.

- Check equipment. Confirm capacity, drum grip type, and inspection status.

- Assess the route. Look for slopes, steps, low beams, and tight corners.

- Assign people. Name the operator, spotter, and supervisor if needed.

- Brief the team. Review hazards, signals, and emergency actions.

A risk matrix helps decide which hazards need stronger controls. Each hazard gets a likelihood rating and a consequence rating. The matrix then gives a risk level, such as low, medium, or high. For example, an 800 kg barrel falling from a poorly clamped forklift drum lifter would rate as low likelihood but very high consequence. That drives stricter controls, such as secondary retention, exclusion zones, and higher sign‑off level.

Site, Load, And Personnel Hazard Identification

Effective risk assessment for how to lift a heavy barrel depends on complete hazard identification. The assessor should walk the route and inspect the load before any lift. Site hazards often include uneven floors, slopes, drains, low doors, and nearby traffic. Outdoor lifts add wind, rain, and poor lighting.

Load hazards relate to the barrel and its contents. Key checks include:

- Accurate weight and center of gravity.

- Condition of the drum shell, chimes, and bungs.

- Labeling for flammable, toxic, or corrosive contents.

- Presence of leaks, bulging, or corrosion.

Personnel hazards focus on how people interact with the lift. Manual pushing, pulling, or rolling heavy drums can cause back strain, crushed toes, or finger injuries. Poor communication between the operator and spotter can lead to people entering the crush zone. The risk assessment should map where people stand, where they walk, and how they escape if the barrel shifts or falls.

Combining these three views gives a realistic picture of risk. A smooth floor and good truck may still be unsafe if the drum is unlabelled and possibly unstable. In that case, the plan must treat the contents as hazardous until confirmed safe.

Control Measures, Permits, And Periodic Review

Control measures convert the risk assessment into safer work. Engineering controls sit at the top. These include using purpose-built electric drum stacker, clamps, and pallets rated above the maximum drum weight. Administrative controls then define how to use them. Examples include standard operating procedures, pre-lift checklists, and clear communication rules between operators and spotters.

For higher-risk lifts, a permit-to-work system adds extra checks. The permit confirms that the route is clear, the ground is stable, and emergency plans are in place. It also records who approved the lift and when it expires. This is useful for heavy, awkward, or hazardous-content barrels.

Periodic review keeps the assessment valid. Supervisors should review incidents, near misses, and changes in layout or equipment. They should then update the risk matrix, lift plans, and training. Simple trend tracking, such as repeated near misses during manual keg handling, can justify investment in better handling aids. Over time, this cycle of assess, control, and review reduces both injury rates and unplanned downtime.

Manual Handling, Ergonomics, And Storage Risks

Manual handling of heavy barrels combines high mass, awkward shape, and often hazardous contents. Poor technique or storage design quickly turns routine work into serious injury or loss events. This section explains how to lift a heavy barrel safely by understanding injury mechanisms, applying ergonomic methods, and designing stable storage layouts.

Injury Mechanisms In Manual Barrel Handling

Heavy barrels create high compressive and shear loads on the spine. A 55‑gallon drum often weighed 180–360 kg, so even small tilts or catches could overload muscles and ligaments. Typical injury patterns included:

- Acute low back strains from bending and twisting while pushing or catching a moving drum.

- Crush injuries to toes and fingers when drums rolled, slipped, or dropped from trucks or pallets.

- Shoulder and elbow disorders from repeated high-force gripping on chimes and rims.

- Chemical exposure when leaking drums were rolled or dragged without inspection and PPE.

How to lift a heavy barrel safely started with avoiding pure lifting. Operators should push, roll, or tilt under control instead of dead‑lifting. Two-person handling reduced peak loads but only if both workers used coordinated moves and clear signals. Untrained helpers often increased risk by unexpected pushes or pulls.

Ergonomic Techniques For Drums And Kegs

Ergonomic practice focused on joint angles, load paths, and task design. The goal was to keep the spine near neutral and use stronger leg muscles. For occasional manual moves, good practice included:

- Reading labels and the safety data sheet before any contact with the barrel.

- Wearing gloves, safety footwear, and eye protection as a minimum set of PPE.

- Positioning feet wide, close to the drum, with knees bent and back straight.

- Using the lower chime as a pivot and “walking” the drum instead of lifting it clear.

For beer kegs and smaller drums, teams often used two-person lifts. They kept the load at belt to mid‑chest height and avoided lifts above shoulder level. Lift gates, small ramps, and low‑friction trailer floors reduced the need to bend or twist. Adjustable hand trucks with nose plates near waist height further cut spinal loading. Training on body mechanics helped workers keep forward trunk flexion within about 10 degrees in normal tasks.

Safe Drum Stacking, Racking, And Access

Storage design strongly affected how to lift a heavy barrel and how often operators needed to touch it. Good layouts reduced manual stacking and unstacking. Typical guidance for 55‑gallon drums limited free‑standing rows to two high and two wide. This height kept stacks stable and allowed visual leak checks.

Key practices for safe stacking included:

| Aspect | Good practice |

|---|---|

| Drum count per pallet | Use consistent patterns, often three drums per standard pallet. |

| Drum size | Stack only same-diameter drums together for symmetry. |

| Interfaces | Place pallets or boards between layers for flat bearing. |

| Restraint | Use chocks or pallet divots to prevent rolling. |

| Access | Maintain clear aisles for trucks and emergency egress. |

Workers should never stack or unstack large drums by hand. They should use appropriate lifting or gripping devices with rated capacity above the drum mass. Racks and floors needed verification for point loads from pallets. Regular inspections checked for corrosion, bulging, and leaks that could weaken containers and destabilize stacks over time.

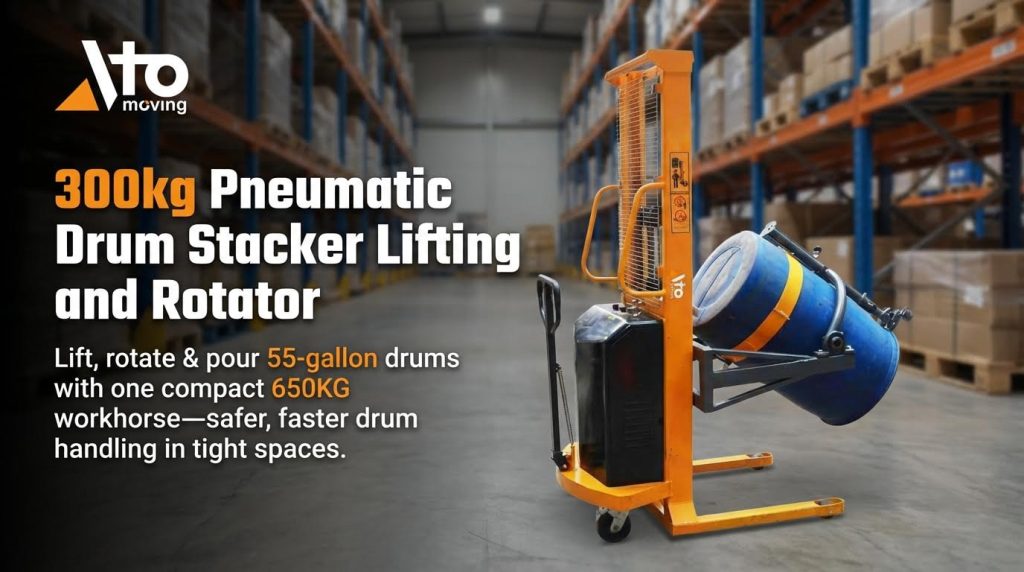

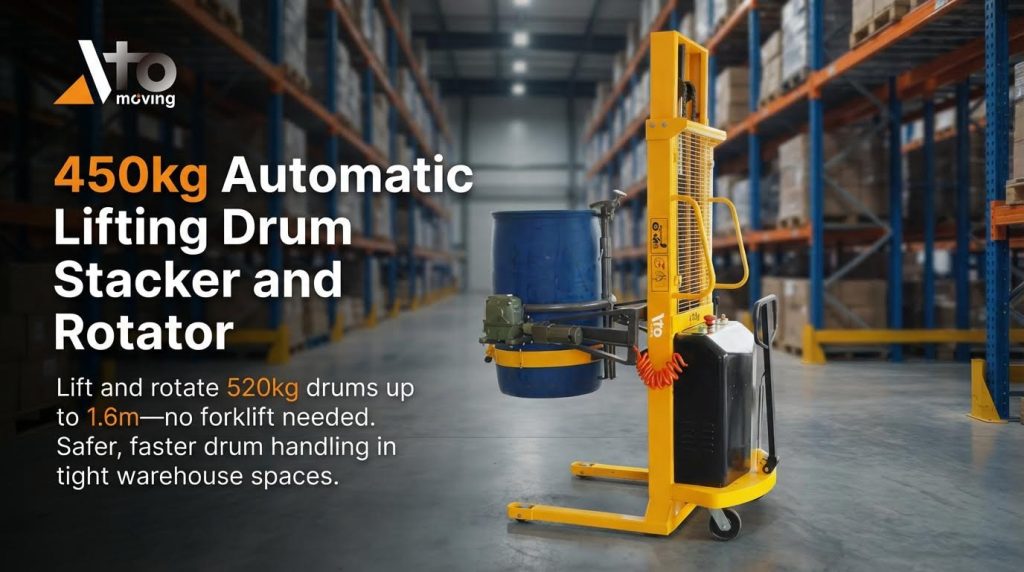

For safer operations, tools like the hydraulic drum stacker, barrel lifter, and forklift drum grabber are recommended to minimize manual handling risks.

Equipment Options For Moving And Lifting Barrels

Engineers who study how to lift a heavy barrel look for repeatable, low-risk methods. Equipment choice affects injury rates, throughput, and product loss. This section compares core options for drum transport and lifting, from pallet trucks to advanced digital twins. It links each option to typical barrel weights, floor layouts, and automation levels.

Comparing Trucks, Drum Lifters, Cranes, And AGVs

When deciding how to lift a heavy barrel, start from load data. A standard 55-gallon drum often weighs 180–360 kg. This weight already exceeds safe manual limits, so mechanical aid is essential. Each equipment family suits a different range of distance, height, and control.

| Equipment | Main role | Typical use case | Key limits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pallet / drum trucks | Horizontal moves | Short runs on flat floors | Limited lift height |

| Dedicated drum lifters | Secure grip and lift | Loading pallets, mixers, or racks | Short travel distance |

| Overhead cranes | High vertical lift | Heavy drums in fixed bays | High capex and fixed path |

| AGVs | Automated horizontal transport | High-volume, repeat routes | Floor quality and layout needs |

Pallet and drum trucks work well when operators roll or tilt drums only at floor level. For frequent vertical moves, dedicated drum lifters give better control and reduce impact loads. Overhead cranes handle extreme weights or tall vessels but need engineered runways and strict signaling. AGVs support unmanned moves of heavy barrels in planned paths, but they still need compatible gripping frames or top modules.

Vertical Drum Lifters And Manual Drum Tippers

Vertical drum lifters answer a core problem in how to lift a heavy barrel safely. They grip the drum by the rim or body and keep it vertical during the lift. This reduces sloshing and avoids sidewall damage. Most devices use mechanical latches or clamps that lock under the drum chime.

Manual drum tippers then handle controlled rotation. Typical designs allow 360° rotation and fine tilt control for decanting. They often support closed-head steel and fiber drums of 30 or 55 gallons with rated capacities around 360 kg. When specifying a model, engineers usually apply a safety factor above the maximum filled drum mass.

For process lines, remote chain controls help operators stand clear of splash zones and pinch points. This also keeps them off ladders, which cuts fall risk. However, these units still rely on hoists, forklifts, or stackers to provide vertical motion.

Industrial Manipulators And Cobot Integration

Industrial manipulators offer a higher-control answer to how to lift a heavy barrel in tight spaces. They combine powered arms with custom grippers that clamp, expand inside the drum, or use vacuum pads. The manipulator carries the drum weight, so operators guide rather than lift.

Compared with simple drum lifters, manipulators add precise positioning, fast cycle times, and complex motions. Typical tasks include lifting from pallets, rotating for dosing, and placing drums into machines with millimetre accuracy. They work well where drum weights exceed ergonomic manual limits but do not justify a full crane system.

Cobot integration extends this concept. A collaborative robot can grip lighter drums or kegs and follow safe speed and force limits around people. Engineers must still verify end-effector ratings, drum center-of-gravity, and collision zones. In mixed environments, clear layouts and interlocks prevent conflicts between forklifts, manipulators, and cobots.

Digital Twins, Sensors, And Predictive Maintenance

Digital tools now support decisions on how to lift a heavy barrel and which equipment to choose. A digital twin can model drum weights, routes, and lift heights in a virtual layout. Engineers test different truck, crane, or manipulator options and see bottlenecks before buying hardware.

Sensors on lifters and cranes track load, tilt angle, and cycle counts. Overload alarms protect against incorrect weight estimates or off-center picks. Vibration and pressure data feed predictive maintenance models, which flag worn bearings, cylinders, or chains before failure.

These tools also support compliance. Logged lifts create traceable records for audits under safety management systems. Over time, data shows which routes, drum types, or operators generate high near-miss rates. Teams can then redesign workflows or upgrade to safer equipment such as guided manipulators or Atomoving solutions where appropriate.

Summary Of Best Practices And Selection Criteria

Safe practice for how to lift a heavy barrel depends on three pillars. These are risk assessment, human factors, and equipment selection. Facilities should document a clear method that joins all three. This method should apply to drums, kegs, and large process barrels.

Key technical lessons are consistent across standards. A formal lift plan and risk assessment should exist for every non-routine heavy barrel lift. The plan should define the load, path, ground conditions, and exclusion zones. It should also assign roles for operator, banksman, and supervisor. A simple risk matrix helps decide when to stop, redesign, or permit the lift.

From an ergonomics view, manual lifting of full 200 litre drums is not acceptable. Workers should only roll, tilt, or “walk” barrels within safe limits. Training should focus on neutral spine, short reach distance, and clear escape routes if control is lost. Storage layouts should limit free-standing stacks to two high and two wide, with stable pallets and chocks.

For equipment choice, engineers should match tools to task frequency and mass. Typical selection criteria include: rated capacity above maximum drum weight, compatibility with drum type, floor and aisle conditions, need for rotation or controlled pouring, and maintenance and inspection access. Simple trucks or basic barrel lifter suit rare, low-risk moves. Manipulators, AGV systems, or integrated sensors suit high-volume or hazardous content.

Future practice will link digital risk assessment, sensor data, and predictive maintenance. This will not remove basic rules for how to lift a heavy barrel. It will support them with better planning, traceability, and safer intervention when conditions change.