Industrial warehouses that ask when stacking drums or barrels how to do it safely must align engineering practice with OSHA rules and fire codes. This article walks through the full framework, from core OSHA 1910.176 and 1926.250 stacking requirements to engineering fundamentals for stable drum, barrel, and keg tiers.

You will see how layout symmetry, blocking, chocking, dunnage, pallet quality, and floor capacity interact to control collapse risk and floor loading. The article then links these design choices to warehouse planning, handling equipment, and digital risk controls that support compliant, high-density storage.

By the end, operations, safety, and engineering teams will share a common standard for when stacking drums or barrels vertically or horizontally, how high they can go, and which controls are mandatory for flammable, corrosive, and high-specific-gravity products. A final summary section consolidates best practices and compliance priorities into a practical checklist for audits and daily inspections.

OSHA Standards And Regulatory Requirements

When stacking drums or barrels in industrial warehouses, OSHA treats the activity as a material storage hazard, not a routine housekeeping task. The core rules in OSHA 1910.176 and 1926.250 focus on preventing sliding, falling, or collapse of stacked loads. Engineers and safety managers must translate these broad clauses into concrete stacking limits, blocking methods, and inspection routines for drums, barrels, and kegs. Fire codes and hazardous material rules then add extra limits for flammable liquids, sprinkler design, and segregation of incompatible chemicals.

Key OSHA 1910.176 And 1926.250 Stacking Rules

OSHA 1910.176(b) and 1926.250(a)(1) set the base requirements for stacked materials. Both standards require tiers to be stacked, blocked, interlocked, or otherwise secured so that loads cannot slide, fall, or collapse. When stacking drums or barrels, this means symmetric layouts, chocking of bottom tiers, and interlocking or containment at higher tiers.

OSHA rules also require clear aisles and safe passageways. 1910.176(a) and 1926.250(a)(3) state that aisles must stay clear and in good repair, with no obstructions that could create hazards. Stacks must never block exits, fire extinguishers, alarms, or electrical panels. Facilities often mark maximum stack heights and clearances with painted stripes or signs so operators can verify compliance visually.

| Requirement | OSHA intent |

|---|---|

| Stacked, blocked, interlocked, secured | Prevent sliding and collapse of drum tiers |

| Limited in height | Keep center of gravity low and stable |

| Clear aisles and exits | Maintain safe egress and equipment access |

| Tidy storage areas | Reduce trip, fire, and pest hazards |

Height Limits, Load Ratings, And Floor Capacity

OSHA does not publish a single maximum height for stacking drums or barrels. Instead, it requires that the weight of stored materials must not exceed the maximum safe floor load. Engineers must check slab design loads, rack ratings, and pallet capacities against the mass of full drums.

Steel drums for hazardous materials must also pass stacking tests under transport rules in 49 CFR 178.606. These tests simulate a stack about 3 metres high for 24 hours at ambient temperature. Typical guidance from drum suppliers has allowed four-high stacks for contents with specific gravity up to about 1.5, and three-high where specific gravity or temperature is higher. Facilities should confirm exact limits with the drum design type, pallet quality, and any racking system used.

When stacking drums or barrels, keep these engineering checks in sequence:

- Confirm drum stacking rating and test basis.

- Verify pallet integrity and drum overhang limits.

- Confirm floor or rack load capacity with safety margin.

- Apply conservative internal height limits and mark them clearly.

Fire Codes For Flammable Liquids And Drum Storage

When stacking drums or barrels that contain flammable liquids, OSHA rules link with fire codes such as NFPA 30. OSHA limits quantities in flammable storage cabinets and expects proper cabinet design, including minimum sheet steel thickness, double walls, and raised sills for spill control. For larger drum arrays, NFPA guidance has required sprinkler protection and, for some palletized steel drum stacks, foam-water systems with defined discharge densities.

Typical code-based practices for flammable drum storage include:

- Keeping hazardous materials separated from exterior walls and incompatible chemicals.

- Maintaining clear space below sprinklers and around piping and lighting.

- Restricting stack height so spray patterns can penetrate the array.

- Using pressure-relieving drum fittings where required by NFPA design.

Stacks of flammable drums must also support emergency response. Layouts must keep access routes open for fire crews and allow quick identification of contents through visible labels and placards.

Penalties, Documentation, And Audit Readiness

OSHA has treated improper stacking and blocked egress as serious violations. Published penalty ranges in the United States have reached tens of thousands of dollars per violation, with higher amounts for willful or repeated cases. When stacking drums or barrels, poor documentation can turn a technical issue into an enforcement problem.

Audit-ready facilities usually standardize three elements:

- Written stacking rules that link OSHA clauses to drum-specific limits, including height, pallet type, and aisle width.

- Visual controls such as floor markings, height stripes on walls or posts, and signage that shows maximum tiers and clearance limits.

- Inspection records that cover pallet condition, drum damage, labeling, leaks, and housekeeping around stacks.

Training is also critical. Operators must understand why chocks, dunnage, and symmetric layouts matter, not just where to place drums. Documented training and periodic refreshers help prove that the facility manages stacking risks systematically, not informally.

Engineering Fundamentals Of Stable Drum Stacks

Engineering teams ask a recurring question: when stacking drums or barrels, what controls real stability. The answer depends on layout symmetry, contact surfaces, containment properties, and how load paths flow into the floor. This section links OSHA style rules with mechanical design practice so warehouses can justify stack heights with calculations, not habits. It focuses on engineering factors that matter across steel, plastic, and fiber containers.

Symmetrical Layout, Blocking, And Chocking Methods

When stacking drums or barrels, symmetry is the first control for stability. Loads should center over pallet stringers and floor joints to avoid eccentric bending. Engineers design patterns so each upper drum bears over at least three lower support points.

Key practices for layout and restraint include:

- Use square or diamond patterns so drum centerlines align vertically.

- Keep identical container sizes within a stack to avoid point loading.

- Align bungs away from contact lines to reduce local deformation.

Blocking and chocking stop low-force shifts that start collapses. Bottom tiers on end need chocks on both sides along the direction of possible movement. Side-stored drums require blocking that resists rolling and spreading, especially under vibration from forklift barrel grabber. Blocking elements must carry shear from the full stack mass with a safety factor that meets internal standards, often 3 or higher.

Vertical Vs. Horizontal Stacking And Dunnage Design

Vertical stacking on end gives compact layouts but creates high contact stress on drum chimes. Horizontal stacking spreads load along the shell but adds rolling risk and more floor area. Engineers choose orientation based on product type, leak risk, and handling method.

When stacking drums or barrels vertically, dunnage design is critical. A good dunnage system:

- Creates a flat interface between tiers using pallets or plywood sheets.

- Distributes load away from narrow chimes into a wider footprint.

- Maintains friction to resist sliding during impact or vibration.

Typical dunnage uses timber planks or structural plywood with stiffness high enough to limit deflection under the top-tier weight. Excessive deflection causes rocking and progressive misalignment. For horizontal stacks, cribbing or wedge blocks must match drum diameter and contact at two or more points to avoid shell denting.

Pallet Specifications, Floor Flatness, And Clearances

Pallet quality sets the real load path when stacking drums or barrels. Engineers specify pallet size, deck board spacing, and entry type to match drum diameters. A common target is four drums on a square pallet with no overhang and full bottom support.

Important pallet parameters include:

| Parameter | Engineering aim |

|---|---|

| Plan size | Full drum base support, no overhang |

| Deck gaps | Limit local bearing stress and sag |

| Stringer strength | Support stacked weight with low deflection |

| Entry type | Four-way entry for efficient forklift access |

Floor flatness and level strongly affect stack stability. Uneven slabs tilt pallets and shift the combined center of gravity toward one edge. Engineering checks usually require:

- Flatness within warehouse flooring tolerances for racking zones.

- No spalling or cracks under high load areas.

- Documented floor load rating above the maximum stacked pallet load.

Clearances above and around stacks must respect sprinkler, lighting, and pipe locations. Vertical clearance also limits practical stack height, even when structural capacity remains.

Specific Gravity, Temperature, And Stack Height Limits

When stacking drums or barrels, the fill material often controls safe height more than the container shell. Specific gravity sets the mass of each filled drum and therefore the compressive load on lower tiers. Higher specific gravity means higher stack stress at the same tier count.

Engineering practice links stack height to three main factors:

- Verified drum stacking test rating for a defined specific gravity.

- Expected maximum ambient temperature in the storage zone.

- Duration of stacking under full load.

As temperature rises, liquid expansion and reduced material strength increase internal pressure and deformation risk. Facilities often reduce stack height when specific gravity exceeds about 1.5 or when long exposure above 30 °C is possible. Engineers should combine supplier stacking test data with conservative safety factors and local fire code limits. Documented limits, posted as height markers or painted bands on walls or posts, help operators keep real stacks within engineered design values.

Warehouse Design, Equipment, And Risk Controls

Warehouse design defines how safe and efficient drum stacking works in practice. Layout, clearances, and equipment choice all affect stability when stacking drums or barrels. Strong risk controls reduce the chance of falling loads, leaks, and fire spread. This section links layout rules with handling methods and digital tools for safer operations.

Aisle Planning, Egress, And Sprinkler Clearance

Engineers should start with aisle planning before deciding how and where to stack drums or barrels. OSHA required that aisles and passageways stay clear, in good repair, and free of tripping hazards. Aisles must not be blocked by stacked materials, pallets, or parked equipment. Access to exits, alarms, and extinguishers must remain visible and open at all times.

Clearances must reflect equipment envelope and load overhang. Forklifts and AGVs need turning space plus side clearance for sway and mast deflection. Designers should consider extra space near columns, racks, and dock doors where impacts often occurred. Marked travel lanes and pedestrian walkways reduce confusion and near misses.

Vertical clearance is critical when stacking drums or barrels under sprinklers. Fire codes and NFPA guidance required a minimum gap between the top of stacks and sprinkler deflectors. This gap allowed water spray to spread and foam-water systems to reach all tiers. Designers should also consider clearance around lighting, ductwork, and cable trays to avoid hidden ignition or snag points.

Housekeeping, Labeling, And Hazard Segregation

Good housekeeping made stable stacks easier to maintain. Flat, clean floors reduced pallet rocking and uneven drum bearing. Debris, shrink wrap, and broken boards increased slip and trip risk near stacks. Storage areas had to stay free of excess materials that could fuel fires or shelter pests.

Clear labeling supported safe decisions when stacking drums or barrels. Labels should show contents, hazard class, specific gravity, and temperature limits. Operators then know whether a drum can go on upper tiers or must stay low. Labels must remain visible after stacking, so layout should avoid hiding key markings.

Hazard segregation is essential for chemical compatibility. Incompatible liquids must not share the same stack or adjacent bays. Typical controls include:

- Separate zones for oxidizers, flammables, and corrosives

- Minimum spacing from exterior walls and drains

- Secondary containment sized for likely spill volume

Segregation rules also apply to empty but uncleaned drums, which can still release vapors or react with residues.

Drum Handling With Forklifts, AGVs, And Atomoving

Handling method strongly affects how high and how tight you can stack drums or barrels. Forklifts remain common for palletized drums. Operators must approach square to the load, keep forks level, and avoid sudden tilts that could shift tiers. Training should stress that impact into stacks can trigger progressive collapse.

AGVs move drums along fixed or mapped routes. They need consistent aisle widths and predictable traffic patterns. Designers should keep AGV paths away from high stacks where contact risk is higher. AGV speed and acceleration profiles should match drum mass and pallet stiffness.

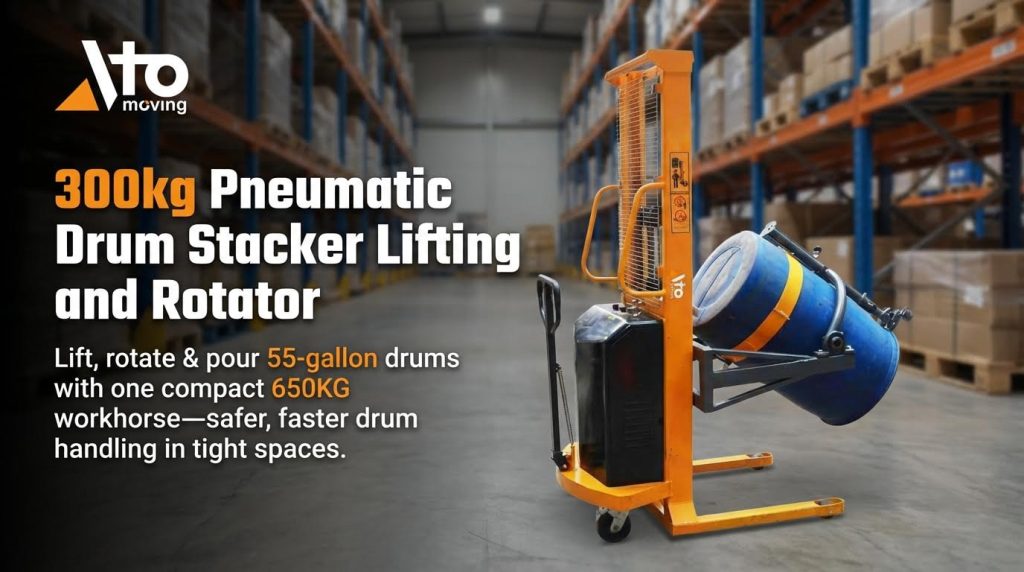

Specialized drum handling equipment, including drum stacker, can grip, clamp, or cradle drums more securely than bare forks. These devices reduce local stress on drum shells and chimes. They also allow controlled rotation between vertical and horizontal positions without manual intervention. When combined with good pallet condition and flat floors, they lower damage rates and leak incidents.

Any handling system should include regular inspection of forks, clamps, and sensors. Wear or misalignment can reduce clamping force and increase slip risk during lifting or travel.

Digital Twins, Sensors, And Predictive Safety Analytics

Digital tools help engineers test “what if” scenarios before changing how they stack drums or barrels. A warehouse digital twin can model load paths, aisle congestion, and evacuation times. Planners can compare different stack heights, pallet patterns, and traffic routes. They can then choose layouts that keep throughput while reducing risk.

Sensors add live data to these models. Options include load cells on racks, floor strain gauges, and pallet or drum tags with tilt or impact sensors. These devices can flag overloaded bays, excessive vibration, or stacks that lean beyond set limits. Temperature and VOC sensors near flammable storage help detect early signs of reaction or leakage.

Predictive safety analytics uses this data to spot patterns. Examples include repeated near misses at the same intersection or frequent impacts on a specific rack line. Algorithms can link these events to root causes such as narrow aisles, blind corners, or aggressive driving profiles. Teams can then adjust speed limits, mirror placement, or traffic rules.

When combined with training and clear procedures, digital systems support a proactive approach. They do not replace OSHA rules or engineering judgment but make it easier to enforce safe stacking plans in busy, changing warehouses.

Summary Of Best Practices And Compliance Priorities

When stacking drums or barrels in industrial warehouses, treat the task as an engineering and compliance problem. The goal is stable stacks, predictable behavior under load, and clear evidence of OSHA and fire code alignment. This summary links the earlier sections into a simple decision framework for daily operations and long term design.

From a technical view, stable stacks start with symmetry, blocking, and floor checks. Engineers and supervisors should verify three points before raising height:

- Layout: symmetric patterns, chocked or blocked base, and suitable dunnage between tiers.

- Capacity: drum test ratings, pallet capacity, and floor or rack load limits.

- Environment: specific gravity, temperature range, and sprinkler or egress clearances.

Regulations have stayed strict while tools have evolved. OSHA rules still required stacks to be blocked, interlocked, and limited in height. Fire codes still controlled flammable drum arrays, cabinet design, and sprinkler demand. Newer trends added digital twins, sensors, and analytics that helped predict tilt, impact, and temperature excursions before failure.

When stacking drums or barrels, implementation must stay practical. Use simple visual cues such as height stripes, load limit signs, and aisle markings. Link written procedures with operator training and periodic stack audits. Combine manual checks with data from sensors or warehouse systems where budgets allow. Technology will keep improving, but conservative heights, good pallets, and clean aisles will remain the core controls for safe drum, barrel, and keg storage.