Facilities that search for how to lift a barrel safely usually face a mix of regulatory, ergonomic, and productivity pressures. This article links global lifting rules with practical methods for handling drums and barrels in workshops, warehouses, and process plants.

You will see how to plan compliant lifting operations, choose the right mechanical aids, and apply rigging and strapping techniques that protect both people and product. The outline also explains when manual handling is acceptable, when it must stop, and how digital tools and maintenance practices support long term safe barrel lifter handling.

Regulatory And Risk Basics For Barrel Lifting

Facilities that search for how to lift a barrel safely must treat it as a controlled lifting operation. This section explains the regulatory frame and risk controls that apply to barrels, drums, and similar containers. It links global rules to practical steps for planning lifts, marking equipment, and proving operator competence. The goal is a repeatable process that keeps people clear of dropped loads and crush zones.

Global Standards: OSHA, LOLER, PUWER, ISO

OSHA rules in the United States treated any barrel lift as a cargo or material handling draft. Loads had to be properly slung, with loose dunnage removed before hoisting. Operators needed clear sight of the load or a signaler, and workers had to stay out from under suspended barrels.

In the United Kingdom, LOLER required every lift to be planned, supervised, and done by competent people. Equipment had to be strong, stable, correctly installed, and clearly marked with its safe working load. PUWER added that work equipment must suit the job, be maintained, and only used by trained staff.

Internationally, ISO and EN standards supported these laws. ISO 9927 covered crane inspection and ISO 23853 covered condition monitoring of lifting equipment. Together they set expectations for regular checks, proof tests, and record keeping for lifting gear used on barrels.

Risk Assessment: Load, Route, And Environment

Before deciding how to lift a barrel, a formal risk assessment was essential. The assessment started with the load itself. Teams checked barrel mass, fill level, shape, and likely centre of gravity position. They noted if the barrel was damaged, leaking, or stacked.

Next they planned the travel route. Engineers looked for slopes, uneven floors, tight corners, and overhead obstructions. They confirmed that the crane, hoist, or truck could move without blind spots or clash risks. They also reviewed escape paths and exclusion zones.

Environmental factors then came into play. Typical checks included:

- Lighting quality along the full route

- Floor condition, including wet or slippery areas

- Wind and weather for outdoor lifts

- Nearby traffic, pedestrians, and other machines

The final step compared risk with control options. If manual handling created high musculoskeletal risk, the plan shifted toward hoists, barrel lifter, or other aids. If the route remained unsafe, the job was redesigned before any barrel left the ground.

Safe Working Load, Marking, And Inspection

Safe working load control sat at the core of any method for how to lift a barrel. Regulations required that no gear worked above its rated SWL. In the United States, cargo gear above 4.54 tonnes SWL had to show its rating clearly. Heavy items above 0.91 tonnes also needed their own weight marked for planning.

Before first use, lifting beams, spreaders, and special barrel gear needed proof load tests. Typical test loads exceeded SWL by 10–25%, depending on capacity range. After structural repairs, the same proof tests applied again. Larger cargo gear over 4.54 tonnes SWL then needed periodic proof tests at set intervals, often four years.

Daily practice relied on simple checks. Operators or riggers inspected hooks, chains, slings, and drum clamps before each shift. They looked for wear, deformation, cracked welds, and damaged tags. Any suspect item was taken out of service until a competent person cleared or repaired it.

Inspection and test records had to be available for review. This paperwork allowed supervisors to prove that every barrel lift used rated, maintained, and traceable equipment.

Training, Competency, And Documentation

Safe barrel lifting depended on competent people as much as on strong gear. Regulations in the UK and US both required trained personnel for planning, rigging, and operating lifting devices. Training covered SWL limits, basic rigging for drums, tag line use, and safe approach distances.

Manual handling training addressed cases where workers still handled light or empty barrels. Courses taught body posture, team lifts, and when to refuse a lift and request a mechanical aid. Refresher sessions kept skills current and corrected poor habits seen in the field.

Competence was not only about courses. Supervisors checked that staff could apply training in real tasks. They confirmed that operators understood signals, emergency stops, and exclusion zones around swinging barrels. Only then were they signed off for independent work.

Documentation closed the loop. Typical records included:

- Lifting plans for non‑routine or complex barrel lifts

- Training and refresher certificates for operators and riggers

- Inspection and test reports for lifting gear

- Incident and near‑miss reports used for lessons learned

With this system in place, sites could show regulators and clients that every step of how to lift a barrel was controlled, recorded, and continually improved.

Mechanical Aids For Lifting And Moving Barrels

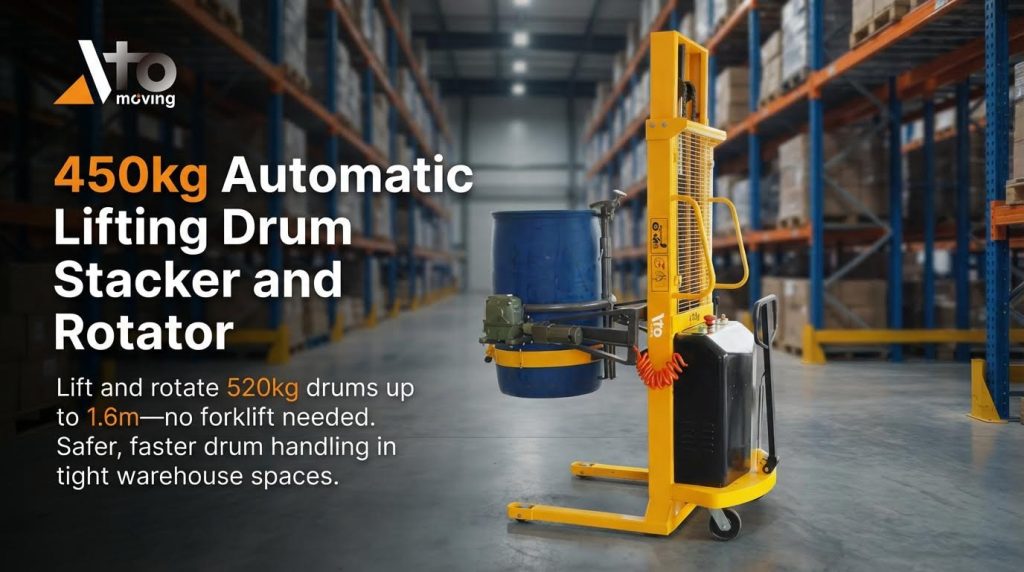

Mechanical aids answer a core question in industry: how to lift a barrel safely and repeatably. They cut manual strain, control load paths, and keep lifting forces within known limits. Engineers select hoists, drum lifters, forklift drum grabber, and automated systems based on barrel mass, route, and duty cycle. Correct choice and setup reduce dropped loads, crush zones, and long‑term musculoskeletal injuries.

When planning how to lift a barrel with mechanical aids, designers first confirm the safe working load of every component in the chain. That includes beam, trolley, hoist, hook, sling, and gripping device. They then match the device to the motion needed: pure vertical lift, combined lift and transport, or tilt and pour. Finally, they define tag line use, exclusion zones, and signal methods so operators never stand under or near suspended barrels.

Chain And Lever Hoists For Vertical Lifting

Chain and lever hoists give controlled force for vertical or near‑vertical barrel lifting. Chain hoists suit fixed stations where barrels move straight up and down on an overhead beam or trolley. Lever hoists work well when space is tight or when the pull direction is not vertical.

Key engineering checks before using hoists to lift a barrel include:

- Confirm rated capacity exceeds barrel weight plus rigging mass.

- Verify the support structure rating and connection details.

- Inspect hooks, latches, and load chain for wear or deformation.

- Check that the operator has clear sight or a trained signaler.

Chain hoists provide fine height control, which helps when placing a barrel on a pallet, into a bund, or onto a process stand. Lever hoists add the ability to tension or pull a barrel sideways over short distances, for example when aligning with a filling line. In both cases, tag lines should guide the barrel and keep hands away from pinch points. Operators must never ride the hook or the load and must keep out of the fall zone under the barrel.

Drum Lifters, Clamps, And Forklift Attachments

Dedicated drum lifters and clamps solve how to lift a barrel with consistent grip and geometry. Vertical drum lifters hang from a hook or hoist and grab the rim or body. They allow lift, rotation, and controlled pour of standard steel or plastic drums.

Forklift drum attachments clamp one or more barrels and let trucks move them horizontally. This improves throughput compared with single‑drum manual moves. Typical engineering considerations include:

| Aspect | Design focus |

|---|---|

| Barrel type | Steel, plastic, or fibre; rim strength and diameter |

| Capacity | Mass per barrel and number of barrels per cycle |

| Stability | Clamp position vs centre of gravity |

| Forklift rating | Residual capacity with attachment fitted |

Safe practice requires secure engagement before lift, no transport over personnel, and smooth acceleration and braking. Operators should avoid sharp turns with raised barrels and should keep loads as low as practical. Pre‑use checks must confirm that clamps lock correctly and that any rotation mechanism works without sticking or backlash.

Cobots, AGVs, And Automated Barrel Handling

Automation has changed how to lift a barrel in high‑volume plants. Cobots can manage lighter drums at workstations, while automated guided vehicles (AGVs) or autonomous mobile robots (AMRs) move unitized barrel loads along fixed routes. These systems reduce human exposure to crush zones, repetitive strain, and chemical spills.

Engineers integrate sensors, interlocks, and speed limits to control risk. For example, vision or lidar sensors detect people or obstacles in AGV paths and trigger controlled stops. Cobots operate at limited speeds and forces so that contact with people remains within safe thresholds.

Automation design for barrel handling often follows this sequence:

- Define payload envelope: barrel mass, dimensions, and centre of gravity.

- Select gripper style: clamp, cradle, or pallet handling.

- Set route and floor conditions: slopes, thresholds, and congestion.

- Program safe zones, warning signals, and emergency stops.

Automated systems still require clear exclusion markings, training, and maintenance. Operators must understand that a robot or AGV cannot compensate for damaged barrels, leaking contents, or overloaded pallets. Those issues need upstream process control and inspection.

Predictive Maintenance And Digital Twins

Predictive maintenance tools and digital twins support safe, low‑cost answers to how to lift a barrel over the long term. Sensors on hoists, clamps, and forklifts track load spectra, run hours, and shock events. Software then flags when components approach fatigue limits or inspection thresholds.

Digital twins mirror the lifting system in software. Engineers use them to simulate different barrel weights, attachment types, and traffic patterns. This helps test layout changes or new product introductions without risking real equipment or people. It also allows analysis of overload scenarios and near misses.

Typical data streams for predictive maintenance include:

- Load cell readings vs rated capacity.

- Lift counts and duty cycles per shift.

- Motor currents, brake temperatures, and vibration levels.

When trends move outside set limits, planners schedule targeted inspections or part replacement before failure. This approach reduces unplanned downtime and supports compliance with inspection rules that demand safe gear, clear markings, and traceable records. Over time, digital models and live data together refine how facilities lift barrels with less risk and higher productivity.

Straps, Slings, And Manual Handling Techniques

This section explains how to lift a barrel safely when using straps, slings, and manual methods. It links rigging practice with ergonomic technique and clear rules on when manual lifting must stop. The aim is to cut injury risk while keeping barrel handling efficient and compliant.

Selecting Slings, Straps, And Tag Lines

Correct sling choice is the first step in how to lift a barrel safely. Always match sling type to barrel size, weight, and surface condition. Check the safe working load (SWL) on the sling tag and keep the total load plus dynamic effects below that value.

For most barrels, operators use:

- Web slings for painted or stainless barrels where surface damage is a concern.

- Chain or wire rope slings for rugged steel barrels in harsh environments.

- Dedicated drum lifting straps or cradles for repeat production work.

Keep sling angles as large as possible to limit leg tension. Angles below about 60° to the horizontal increase sling forces quickly. Use tag lines when the barrel needs manual guidance. Tag lines must be long enough so workers stay clear of the drop zone and suspended load.

Inspect slings and straps before each use. Remove any gear with cuts, broken wires, crushed fittings, or missing tags from service until repaired or replaced.

Rigging Practices For Drums And Unitized Loads

Rigging practice decides whether a barrel lift stays stable or fails. Always center the hook above the barrel’s centre of gravity. This reduces swing and side pull on the lifting gear.

For single loose barrels:

- Use purpose-designed drum slings, clamps, or cradles where possible.

- Avoid choke hitches around the barrel body unless the sling and drum design allow it.

- Keep the barrel upright unless the lift plan clearly allows tilting.

For unitized loads on pallets or in stillages, treat the unit as one rigid load. Only lift from bands or straps if they are rated and marked for lifting. If banding looks damaged, add extra slings or a pallet bridle to hold the unit together.

Before lifting, remove loose dunnage that could slip out and unbalance the load. Use positive connection hardware such as shackles or hooks with safety latches. Never rely on friction alone between sling and barrel rim.

Ergonomic Manual Techniques And Team Lifts

Manual technique matters whenever operators ask how to lift a barrel without machinery. Manual handling must only occur with empty or light barrels. Heavy or full barrels need mechanical aids or drum lifting equipment.

For up-ending or tilting a light drum:

- Stand close to the drum with one foot forward and one back.

- Bend hips and knees while keeping the back straight.

- Hold the rim low, near the floor, with elbows inside the knees.

- Use leg drive and body weight to rock the drum to its balance point.

Keep the drum close to the body to reduce leverage on the spine. Avoid twisting. Turn the feet instead. For a full drum, use a team lift if no mechanical aid is available. Two workers should mirror each other on opposite sides and lift in a slow, agreed sequence.

Ergonomic programs should include training, task rotation, and simple warm-up routines. These steps lower fatigue and reduce the rate of back and shoulder injuries.

When Manual Handling Must Be Prohibited

There are clear limits on how to lift a barrel by hand. Manual lifting must stop when risk cannot be controlled to an acceptable level. Typical stop points include:

- Full barrels above local manual handling weight limits.

- Stacked drums that need lifting or lowering from height.

- Barrels with unknown contents or shifting liquid that changes the centre of gravity.

- Routes with slopes, steps, poor lighting, or slippery floors.

In these cases, use hoists, drum trucks, forklifts with forklift drum attachments, or Atomoving automated systems. Supervisors should enforce a simple rule. If the barrel weight, posture, or route looks unsafe, manual lifting is not allowed.

Document these rules in lifting plans and safe systems of work. Train operators to stop the job and request mechanical help rather than improvise a manual lift under pressure.

Summary: Safe, Efficient, And Compliant Barrel Lifting

Safe barrel lifting depends on three linked pillars. These are regulation, engineered equipment, and disciplined manual practice. Anyone asking how to lift a barrel must treat it as a controlled lifting operation, not a casual task.

From a regulatory view, OSHA, LOLER, PUWER, and aligned ISO standards required planned lifts, marked safe working loads, and recorded inspections. Gear had to stay within its rated capacity and pass proof load tests before and during service. Tag lines, clear sight lines, and exclusion zones under suspended loads reduced impact and crush risk. Documentation, training, and refreshers proved that operators stayed competent over time.

Mechanical aids such as hoists, barrel lifter, clamps, forklift barrel grabber, cobots, and AGVs turned heavy barrel moves into repeatable processes. Vertical handling, tilting, and rotation became predictable and less dependent on operator strength. Digital twins and condition monitoring helped schedule maintenance before failure and supported higher equipment uptime.

Straps, slings, and manual methods still had a role but under strict limits. Correct sling selection, positive attachment, and tag line control kept unitized loads stable. Ergonomic techniques and team lifts only applied to light or empty barrels on good floors. Full, stacked, or unstable barrels required mechanical lifting or automated systems. Future improvements would combine smarter sensors, safer gripping devices, and clearer procedures so facilities could lift barrels faster while staying compliant and protecting workers.