Industrial teams that search for how to use a barrel lifter usually handle heavy drums daily under tight safety rules. This article explains the full engineering picture, from basic drum types and load ranges to typical use cases in warehouses, chemical plants, docks, and construction sites.

You will see how manual, semi-electric, and electric drum stacker compare with forklift drum grabber, mobile handlers, and overhead drum hoists for different drum sizes and duty cycles. Later sections detail working load limits, safety factors, and how OSHA and ANSI rules shape inspection, operation, and maintenance programs.

The final guidance section ties these points together into clear selection and best practice rules, so engineers, EHS teams, and operations managers can choose and use drum lifters and hoists safely and efficiently. Throughout, the focus stays on practical design limits, stable handling, and disciplined preventive maintenance rather than brand-driven features.

Drum Lifting Fundamentals and Use Cases

Drum lifters solve a simple problem. They move heavy drums safely and repeatably. Anyone learning how to use a drum lifter must first understand drum types, load ranges, and where these tools work best. This section builds that base before later sections cover equipment types, standards, and maintenance.

Common Drum Types and Typical Load Ranges

Drum lifters handle three main drum families. These are steel drums, plastic drums, and fiber drums. Typical industrial sizes are 30-gallon and 55-gallon drums, but local practice may vary. Most lifters grip the drum rim, body, or chime, so drum geometry matters.

Load ranges depend on drum volume and product density. A full 55-gallon drum of water-based liquid weighs roughly 200 kilograms. Higher density chemicals or oils increase this mass. Many manual drum stackers lift up to about 50 kilograms. Larger hydraulic or electric units often handle 300 to 450 kilograms safely, with some below-hook drum handlers and rotators rated near 450 to 600 kilograms.

When you plan how to use a drum lifter, match its Working Load Limit to the heaviest filled drum plus any attachments. Never rely on empty drum weight. Check labels, Safety Data Sheets, or process specs to confirm real product density.

Key Applications Across Industrial Sectors

Drum lifters support any process that fills, stores, or transfers liquids and bulk solids. Warehouses use mobile handlers to unload trucks, build storage rows, and feed production lines. Construction and marine sites use forklift attachments and hoists where ground conditions are uneven or space is tight.

Chemical and petroleum plants use rotators and below-hook handlers for charging reactors, blending tanks, and waste drums. Food and pharmaceutical sites use stainless or coated lifters to handle ingredients where hygiene rules apply. In each sector, the same basic steps repeat:

- Approach the drum with the lifter aligned to the centerline.

- Engage the clamp, jaws, or sling at the designed contact points.

- Test-lift a few centimetres to verify balance and grip.

- Travel at controlled speed and set the drum down on a stable surface.

These repeatable steps reduce manual handling and standardize risk control across shifts and locations.

Risk Profile of Manual Versus Powered Handling

Manual drum handling relies on body strength, crowbars, or simple dollies. This approach creates high risk for back injuries, crushed feet, and uncontrolled drum rolls. As drum mass rises above about 50 kilograms, manual movement becomes hard to control, especially on slopes or rough floors.

Manual drum lifters and hydraulic stackers reduce strain but still need operator effort. The main risks shift to improper engagement, side pulling, or overloading the device. Powered drum lifters, including semi-electric and electric stackers or overhead hoists, remove most lifting effort. They introduce new hazards such as pinch points, electrical faults, and higher kinetic energy during travel.

When you learn how to use a forklift drum grabber safely, focus on three controls. First, keep loads within the rated capacity with a clear safety margin. Second, use slow, deliberate movements, especially during tilting and pouring. Third, keep clear walkways and guard exposed moving parts wherever regulations require. This balance of ergonomic benefit and machine control defines the modern risk profile for drum lifting work.

Types of Drum Lifters and Hoists

This section explains how to use a drum lifter safely in different layouts. It compares main equipment groups and shows which type fits each duty profile. Focus stays on load range, control method, and control of tilt or rotation. This helps engineers match drum lifters and hoists to real plant needs.

Manual, Semi-Electric, and Electric Drum Stackers

These stackers support vertical lifting, stacking, and short moves. Manual units use a foot pump or hand pump and suit light drums or low lift heights. Typical capacity ranges from about 50 kilograms up to 300 kilograms. Lift heights usually stay below 1.4 metres.

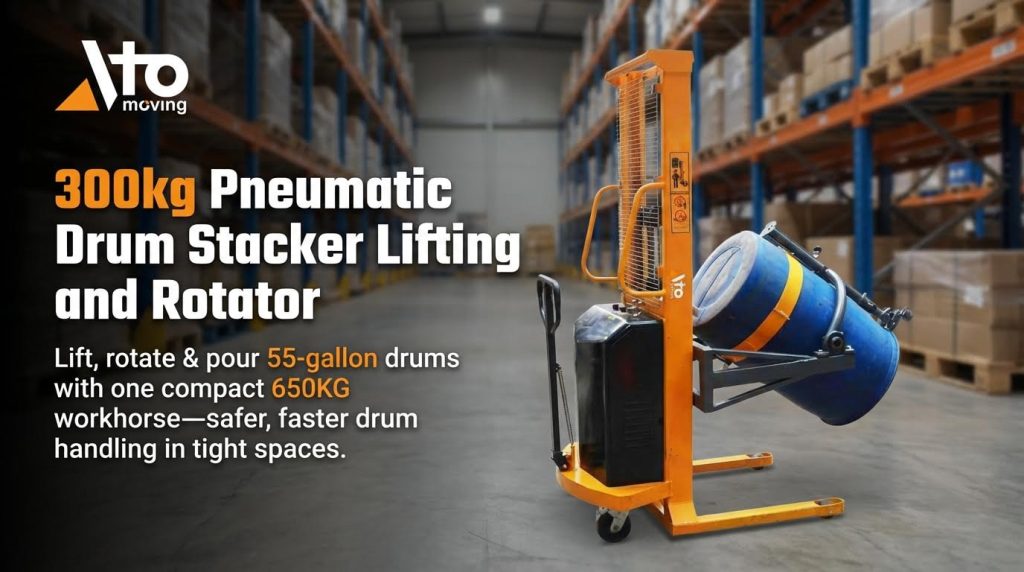

Semi-electric stackers use a motor for lifting and tilting but still push by hand. They fit mid-duty work where floors are tight and cycle counts are moderate. Fully electric stackers power lift, travel, and rotation. These units handle higher loads, often up to about 450 kilograms, and reduce operator strain.

When deciding how to use a drum lifter of this type, engineers check three points. First, match rated capacity to the heaviest full drum, including any residue or liners. Second, confirm lift height clears racking, mixers, or hoppers. Third, verify turning radius and leg spacing match aisle width and pallet layout.

Forklift Attachments, Rotators, and Mobile Handlers

Forklift drum attachments turn a standard truck into a drum lifter. Clamp or grip heads lock onto the drum rim or body. This method suits high-throughput sites that already run forklifts. Operators must keep drums within the truck rated load centre to avoid tip risk.

Drum rotators add tilt or full 360 degree rotation. They support mixing, decanting, or complete emptying of 200 litre drums. Mobile drum handlers work as stand-alone carts or stackers. They move single drums through tight spaces where forklifts cannot enter.

To use a drum lifter in this group safely, operators follow a set sequence. They approach square to the drum. They centre the grip at the marked pick point. They lift just clear of the floor and test stability before travel. Travel speed stays low, especially on ramps or uneven floors.

Overhead Drum Hoists, Slings, and Chain Lifters

Overhead systems pick drums from above using cranes or monorails. Chain drum lifters and slings attach to the drum chime or body. Typical capacities reach from about 450 kilograms up to around 900 kilograms for single drums. Designs often use grade 80 chain and positive latches.

Slings and three arm grabbers centre the drum under the hook. They work well over pits, mixers, or process vessels. Chain and sling angles matter. Wide angles increase tension and can overload fittings even when the drum mass is low.

When planning how to use a drum lifter overhead, engineers check top clearance, hook travel, and swing control. Tag lines help control rotation during lift and set-down. All hooks, shackles, and chains must show clear markings and pass regular inspections. Operators avoid side pulls and keep the hoist line vertical.

Specialized Drum Devices for Tilting and Pouring

Tilting and pouring devices focus on controlled discharge. Common designs clamp the drum in a cradle and add a gear, chain, or motor drive. Manual units allow about 180 degree tilt. Powered models often allow full 360 degree rotation for blending or full emptying.

These devices mount on stackers, forklifts, or overhead hooks. They support repeatable pour angles into kettles, reactors, or smaller containers. Some units include scales to weigh contents during transfer. Others include locking pins to hold a set tilt angle.

Safe use starts with balanced loading. Operators centre the drum in the cradle and secure all locks before lift. They stand clear of the pour path and keep hands off pinch points near gears and chains. Flow control is steady and slow to avoid surge, foam, or splashing of chemicals. For viscous products, engineers may specify higher torque drives and stronger cradles to handle extra bending loads.

Load Limits, Standards, and Safe Operation

Load limits and safety rules decide how to use a barrel lifter correctly. Engineers must match drum mass, lift height, and duty cycle to rated capacity. Standards from OSHA and ANSI define how hoists and lifters must perform and how operators must use them. This section explains how to size, inspect, and maintain drum lifters and hoists so handling stays within safe limits in real sites.

Determining Working Load Limit and Safety Factor

When learning how to use a drum lifter, start with the working load limit. The working load limit, or WLL, is the maximum mass the device may lift in service. Manufacturers set WLL by dividing the minimum breaking load by a safety factor. Typical safety factors for lifting gear range from 4:1 to 10:1, depending on standard and duty class.

Engineers must compare WLL with the heaviest drum plus contents. For example, a 55-gallon steel drum with liquids can approach 250–300 kilograms. Add any extra tools, slings, or attachments to the total load. Never guess mass; use pallet weighing scales or certified data sheets.

To keep margins, apply these steps when selecting or checking a drum lifter:

- Confirm the rated capacity on the nameplate or data sheet.

- Use the highest possible drum mass, not the average mass.

- Derate capacity for off-centre picks or tilted drums.

- Do not exceed rated lift height or outreach stated by the maker.

Side loading, shock loading, and sudden stops increase effective load on chains, gears, and frames. Operators should lift smoothly and avoid jerks. If any doubt exists about mass or rigging angle, choose a higher-capacity lifter or reduce the load per lift.

OSHA and ANSI Requirements for Drum Hoists

OSHA and ANSI rules give the legal frame for how to use a drum lifter and hoist. For base-mounted drum hoists, 29 CFR 1926.553 set design, installation, inspection, and operation rules. The regulation required exposed moving parts, such as gears and chains, to be guarded. It also required controls to sit within easy reach of the operator station.

Electric motor-driven hoists needed a device that cut all power if supply failed. The motor could not restart until the control handle returned to the off position. Where relevant, hoists needed overspeed protection so the drum could not spin faster than design speed. Remotely operated hoists had to stop if any control failed or became ineffective.

Modern ANSI hoist standards typically cover:

| Aspect | Typical requirement |

|---|---|

| Design factor | Safety factor on load-bearing parts |

| Braking | Automatic brakes that hold rated load |

| Controls | Fail-safe logic and clear markings |

| Testing | Proof load tests above rated capacity before service |

Base-mounted drum hoists used with derricks must follow 29 CFR 1926.1436(e) instead. Safety managers should keep current copies of OSHA and ANSI texts and align site rules with them.

Pre-Use Inspection and Operator Checklists

Safe practice for how to use a drum lifter always starts with a pre-use check. A short five-minute inspection can prevent most failures. Operators should follow a written checklist and record findings. Visual checks should cover the frame, mast, welds, and drum gripping parts for cracks, bends, or corrosion.

Mechanical and load path items need close attention. Inspect hooks, chains, bolts, and wire ropes for wear, deformation, or fraying. Check drum clamps, arms, and gripping jaws for smooth action and full closure. Verify that brakes hold the empty lifter and a light test load without creep.

Control and safety systems also need a quick function test. Operators should:

- Test up, down, tilt, and rotate functions without a drum first.

- Check emergency stop and any limit switches.

- Confirm that guards cover gears, chains, and pinch points.

- Verify wheels or outriggers roll and lock correctly.

Any abnormal noise, jerky motion, oil leak, or damaged label is a stop signal. Tag the lifter out of service and report it. Never bypass interlocks or use makeshift slings on a drum lifter that is not rated for them.

Preventive Maintenance and Predictive Monitoring

Planned maintenance keeps drum lifters and hoists safe through their life. Preventive maintenance uses fixed intervals for cleaning, lubrication, and part checks. Predictive monitoring uses actual condition data, such as sound, temperature, or vibration, to plan repairs before failure.

Lubrication has a strong impact on life. Proper grease or oil on gears, bearings, and chains can extend service life by large margins. A common rule for lifting gear is to lubricate at least every 250 operating hours or once per month. Use lithium-based grease for high-load gears and suitable oils for the site temperature.

Maintenance tasks should include:

- Check structural parts for rust, cracks, and loose fasteners.

- Inspect hooks, chains, and wire ropes for wear and corrosion.

- Test brakes, limit switches, and emergency stops under light load.

- Verify electrical cables, connectors, and battery levels on powered units.

Real-time monitoring by trained operators is also vital. Metallic grinding can point to bearing failure. Irregular humming can signal voltage issues. Erratic drum motion can show rigging or brake problems. Shut down at once if these signs appear. Professional inspections at least yearly, or more often for heavy use, support long-term safe operation and reduce unplanned stops.

Summary of Best Practices and Selection Guidance

Engineers who ask how to use a barrel lifter safely should link equipment choice with task risk. Best practice starts with a clear match between drum type, mass, and lift path. Closed-head steel drums, plastic drums, and fiber drums each need compatible gripping geometry and surface pressure. Operators should confirm rated capacity, lift height, and rotation limits before any lift.

Selection should follow a simple logic. Manual or hydraulic units suit low-throughput work and lighter drums. Semi-electric units fit medium-duty tasks with frequent lifting and short travel. Fully electric or overhead hoist solutions suit high-throughput lines, longer travel, or heavy drums near the upper capacity range. A short table helps frame the decision.

| Aspect | Key consideration |

|---|---|

| Load mass | Stay below rated capacity with at least 25% margin |

| Lift height | Check pallet, rack, or vessel lip height plus clearance |

| Rotation | Need 180° tilt or full 360° pour control |

| Duty cycle | Occasional, daily, or continuous shifts |

| Power | Battery, mains, or fully manual |

Safe use depends on routine controls, not just design. Operators should complete a short pre-use checklist that covers brakes, clamps, chains, and any electrical controls. They should verify drum engagement with a test lift a few centimetres above the floor. Clear travel routes, level floors, and controlled speeds reduce tip risk. For hoists, controls must be within easy reach and stop the motion if a control fails.

Preventive maintenance keeps drum transporter reliable across years of service. Lubrication, corrosion checks, and periodic professional inspection limit unexpected failures. Facilities that log inspections and near-misses gain data to refine equipment choice and training. Over time, a move from manual to powered or overhead systems often follows rising drum counts and tighter safety goals. The best solution balances capacity, ergonomics, and regulatory compliance while keeping operation simple for front-line staff.