Facilities that searched for how to move drums safely usually faced a mix of ergonomic, chemical, and mechanical risks. This article used engineering methods to control those risks from first hazard identification through to layout design.

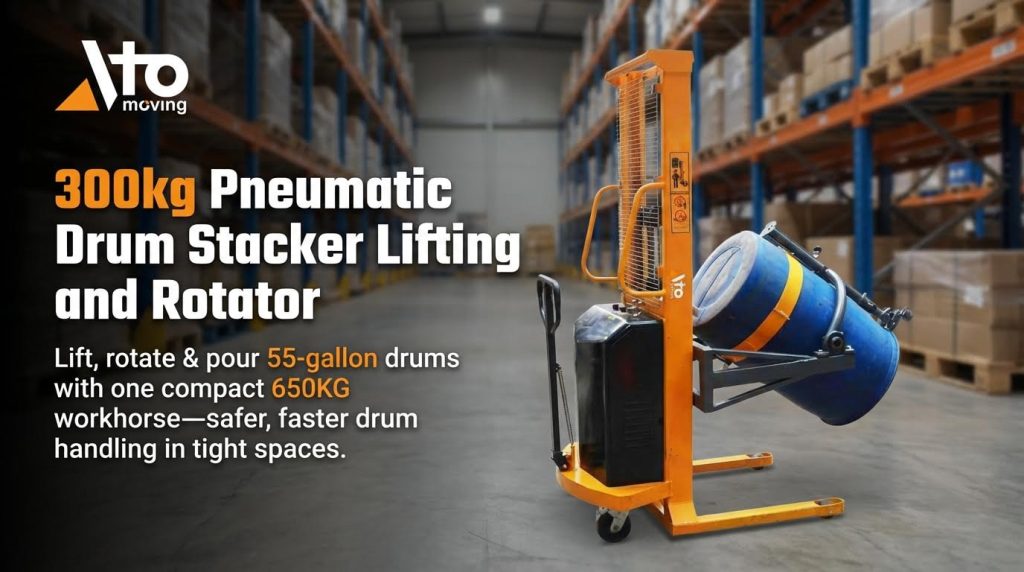

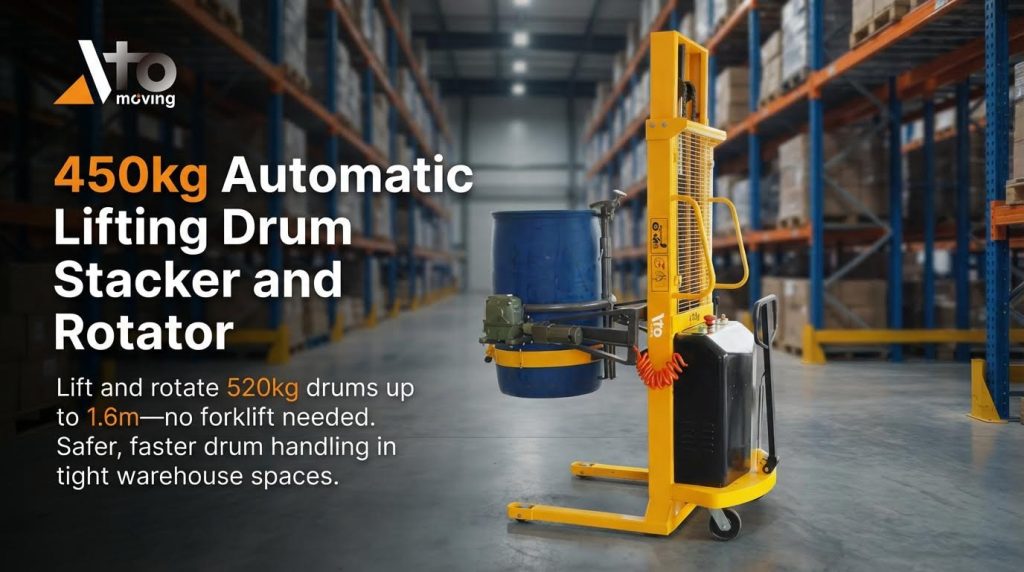

You saw how drum types, fill levels, and regulations shaped basic handling rules, and how engineered moving, lifting, and tipping methods reduced both damage and injury rates. The storage and stacking section then linked stack geometry, aisle design, and ignition control to robust facility layouts. For instance, equipment like the hydraulic drum stacker or a forklift drum grabber can significantly improve safety during drum movement. Additionally, using a drum dolly ensures stability and minimizes manual strain.

The final summary section pulled these threads together into a single drum handling system view so safety, operations, and engineering teams could align on one consistent, defensible standard for damage‑free movement.

Hazard Identification And Regulatory Context

Facilities that study how to move drums safely must first understand what can fail and why. This section explains how drum design, contents, and regulations shape safe handling limits. It links chemical hazard data with OSHA, HSE, and ATEX rules so engineers can set robust site standards. The goal is a clear risk picture before any drum leaves the floor.

Drum Types, Fill Levels, And Failure Modes

Different drum designs react very differently under impact, tilt, or drop. Common industrial types include:

- Steel tight-head and open-head drums for flammable or high-value liquids

- Plastic high-density polyethylene (HDPE) drums for corrosives

- Fiber drums for dry, lower-risk products

When planning how to move drums safely, engineers must match handling methods to drum strength. Key variables are fill level, internal pressure, and wall stiffness. Overfilled drums can build pressure with temperature rise and vent at bungs or seams. Underfilled drums slosh, which shifts the centre of gravity and increases overturn risk on slopes or during sudden stops. Typical failure modes include chime deformation from side impact, bung thread stripping, and seam rupture after drops or point loading. Design reviews should document allowable tilt angles, lift points, and stacking limits for each drum family.

Chemical Hazards, SDS Review, And Labeling Gaps

How to move drums safely depends first on what is inside, not on the metal or plastic shell. Safety Data Sheets describe flammability class, toxicity, corrosivity, and reactivity. Engineers should extract at least:

- Flash point and vapour pressure for fire and explosion risk

- Inhalation and skin exposure limits

- Incompatible materials that affect storage zoning

Before any move, labels must be legible and match the SDS. If labels are missing or unclear, treat the drum as containing hazardous material until analysis proves otherwise. That means upgraded PPE, conservative exclusion zones, and spill kits sized for full drum volume. A simple label verification step at the start of each shift reduces wrong-location storage, mixed-incompatible loads, and incorrect emergency response. Sites should keep a quick-reference matrix that links SDS hazard classes to approved handling routes, maximum manual interaction, and required supervision levels.

OSHA, HSE, ATEX, And Site-Specific Standards

Regulations give the baseline for how to move drums safely, but each site usually needs tighter limits. OSHA material handling rules required stacked drums to be blocked, interlocked, and limited in height to prevent sliding or collapse. HSE guidance in the United Kingdom set similar expectations for manual handling thresholds, floor conditions, and housekeeping. In potentially explosive atmospheres, ATEX rules required that handling equipment, earthing, and work practices prevent ignition sources.

For engineering teams, a useful approach is to map each regulation to design and procedural controls. Examples include:

| Regulatory focus | Engineering control |

|---|---|

| Stack stability | Defined stack geometry, chocking, and documented load ratings |

| Manual handling | Weight limits and mandatory use of manual pallet jack above set masses |

| Explosion risk | Conductive floors, bonding, and non-sparking tools in zones |

Site standards should then tighten these where risk is higher, for example in mixed-chemical warehouses or older buildings with weaker slabs.

Risk Assessment, Zoning, And Permit-To-Work

A formal risk assessment links the question of how to move drums safely with real plant layouts and workflows. The assessment should consider drum mass, traffic density, slope, floor condition, and nearby ignition sources. Outcomes feed into zoning. Typical zones include flammable liquid storage, corrosive handling areas, and high-traffic transfer points. Each zone then gets defined controls such as speed limits, exclusion distances, and minimum PPE.

Permit-to-work systems add another layer for non-routine or high-risk tasks. Examples are moving damaged drums, handling unknown contents, or working inside ATEX-classified rooms with temporary equipment. A permit should check that SDS data is reviewed, spill response is ready, and lifting gear is rated and inspected. It should also confirm that only trained staff enter the area and that emergency routes stay clear. This structure turns individual drum moves into a controlled process rather than an improvised activity.

Safe Drum Moving, Lifting, And Tipping Methods

This section explains how to move drums safely by combining ergonomic limits, dedicated handling devices, and controlled tipping methods. The focus is on full steel or plastic drums between 200 litres and 250 litres, which exceed safe manual lifting limits and require engineered controls.

Manual Handling Limits And Ergonomic Controls

Industrial drums often weigh 180 kilograms or more when full. This far exceeds typical manual handling guidance of 25 kilograms for men and 16 kilograms for women. Direct lifting or carrying of full drums is therefore not acceptable as a routine method.

When planning how to move drums safely, treat manual effort as positioning and guiding only. Workers should roll drums on the chime for short distances, not drag or push on the sidewall. They should keep hands on the far side of the chime, avoid crossing hands, and bend the knees while keeping the back straight during any controlled lowering.

Engineering controls should reduce push–pull forces, twisting, and stooping. Typical controls include:

- Clear, level routes without steps, holes, or steep slopes.

- Limits on maximum distance for any manual rolling task.

- Two-person techniques for up-ending partial drums when no device is available.

- Training on body posture, hand positions, and communication.

Supervisors should treat any task that needs sustained force or awkward postures as a trigger to introduce handling equipment.

Dedicated Drum Trucks, Dollies, And Fork Attachments

Dedicated drum handling devices are the primary answer to the question of how to move drums safely in most plants. These devices convert heavy vertical loads into rolling or supported loads with low operator effort. They also keep the drum upright and reduce spill risk if a bung loosens.

Common solutions include drum trolleys, dollies, and carts that clamp or cradle the drum. Operators keep an upright posture and steer using both hands on the handle. The drum stays balanced over the wheels, which reduces tipping moments on uneven floors.

Forklift drum attachments allow a truck to grip one or more drums without manual contact. Typical attachment types include:

- Rim grip or beak type for steel drums.

- Belt or cradle type for plastic or fibre drums.

- Clamp attachments for mixed drum fleets.

Before use, operators should check that the attachment is compatible with drum diameter, surface condition, and fill level. They must keep the load low, centred close to the mast, and within the rated capacity of both truck and attachment. Routes must avoid tight turns on ramps, which can overload the outer wheel set and destabilise the drum.

Hoists, Grabs, Rotators, And SWL Verification

Where drums move between levels or into process vessels, hoists and grabs control vertical lifting. Each lifting accessory must display a Safe Working Load. The combined mass of drum, product, and any mixer or lance must stay below the lowest SWL in the lifting chain.

Typical drum lifting devices include:

- Vertical drum clamps that grip the chime.

- Horizontal drum grabs for side-lifted drums.

- Rotators that allow 120 degrees to 360 degrees rotation for emptying.

Before every lift, operators should verify four points: correct SWL, correct drum type, secure engagement, and clear exclusion zones. They should lift a few centimetres first to prove balance and grip. Loads should stay as low as practical while travelling to limit swing and overturning moments.

Rotators must have positive locking in both transport and discharge positions. Gearboxes, chains, and structural frames need regular inspection for wear, cracks, and deformation. Any sign of slip, misalignment, or unusual noise is a reason to stop and quarantine the device until a competent person inspects it.

Controlled Tipping, Decanting, And Spill Containment

Decanting is often the highest-risk step when people ask how to move drums safely in liquid transfer areas. The risk comes from sudden flow, splash, or drum movement as the centre of gravity shifts. Engineering controls should therefore manage both motion and containment.

Dedicated drum tippers or rotators hold the drum with clamps or bands before rotation starts. Operators should never stand in the direct discharge line. They should work from the side and use slow, smooth motions on the control lever or hand wheel.

Good practice for controlled tipping and decanting includes:

- Using funnels, taps, or valves rather than free pouring where possible.

- Placing the receiving vessel inside a sump or spill pallet with at least the drum volume capacity.

- Checking bungs, lids, and gaskets for damage before rotation.

- Confirming emergency stop and brake functions on powered tippers.

Surfaces around decanting stations should be non-slip and chemically resistant. Spill kits with absorbents and neutralisers must sit within easy reach. After each transfer, operators should return the drum to a stable position, isolate equipment, and clean any residue so the next move starts from a safe, tidy state.

Stacking, Storage Layout, And Facility Design

Stacking and storage design strongly affect how to move drums safely inside a plant. Poor layouts increase manual handling, blind spots, and impact loads from trucks and forklifts. Engineering controls in stacking, aisle planning, and fire protection help keep heavy drums stable, visible, and accessible. This section links storage geometry with safe handling routes, spill control, and long‑term asset protection.

Stack Geometry, Chocking, And Stability Criteria

Drum stack geometry must limit height and control load paths. For 200 litre or 55 gallon drums, many safety guides recommended a maximum of two high and two wide for free‑standing rows. This pattern allowed visual inspection for leaks and reduced collapse risk from variable drum strength or dented chimes. Symmetrical stacks with aligned drums shared vertical loads better and reduced point stresses on the shell.

Chocking and blocking were essential when drums were stacked more than one tier. Engineers usually required:

- Chocks on both sides of the bottom tier when drums stood on end.

- Blocking or racks when drums lay on their sides to stop rolling.

- Dunnage such as planks, plywood, or pallets between tiers.

Dunnage created a flatter bearing surface and spread forces from upper drum chimes. It also improved friction and reduced creep under vibration from traffic. Stability checks needed to consider floor flatness, pallet stiffness, and impact from handling equipment. OSHA rules required materials stored in tiers to be stacked, blocked, interlocked, and limited in height so stacks resisted sliding or collapse.

Aisle Design, Clearances, And Load Rating Signage

Aisle layout defined how to move drums safely without side impacts or pinch points. Clear, straight aisles reduced steering corrections and sudden braking by forklifts or drum trucks. Designers kept aisles wide enough for the largest handling unit plus clearance for pedestrians. They also avoided dead ends that forced reversing with suspended or palletized drums.

Good practice kept aisles and exits free of stored material at all times. Drums never blocked fire extinguishers, alarms, or spill kits. Floors stayed level, clean, and free of hoses, cables, or debris that could destabilize trolleys. Overhead, engineers checked clearances to lights, pipework, and sprinkler heads to prevent impact from raised forks or hoisted drums.

Load rating signs supported safe decision‑making. Typical controls included:

- Floor load limits in kilonewtons per square metre near storage zones.

- Racking bay and beam safe working loads.

- Maximum stack heights or drum tiers marked on walls or posts.

Visual markers such as painted stripes helped operators judge safe stack height quickly. Combined with traffic routes and one‑way systems, these measures cut collision risk and kept drum movements predictable.

Fire, Explosion, And Static Control In Storage

Storage design for flammable or reactive contents shaped both stack layout and handling methods. Segregation by compatibility reduced the chance of mixed spills that reacted violently. Designers grouped oxidizers, acids, bases, and flammable liquids in separate, clearly marked zones. Spill containment bunds or sumps sized for a defined percentage of stored volume limited spread if a drum failed.

Fire loading and sprinkler coverage drove rack height and density. High stacks under low sprinklers reduced water effectiveness and increased heat build‑up. Many facilities therefore used lower stack heights for flammables and wider spacing between rows. Non‑sparking tools and equipment, plus earthing and bonding of drums and handling gear, helped control static build‑up during movement and decanting.

In potentially explosive atmospheres, equipment had to avoid ignition sources. This included:

- Using conductive or anti‑static wheels and surfaces on drum handling tools.

- Fitting earthing chains to mobile equipment where appropriate.

- Keeping electrical gear and truck exhausts compliant with area classification.

Good ventilation limited vapour concentration in aisles and decanting points. Clear emergency routes allowed fast evacuation if a fire or explosion risk developed.

Housekeeping, Inspection, And Preventive Maintenance

Housekeeping standards directly influenced how to move drums safely day to day. Clean, dry floors reduced slip and tip events when pushing drum dollies or pallet trucks. Storage rows that stayed tidy allowed quick leak detection and avoided hidden trip hazards behind drums. Waste packaging, damaged pallets, and used absorbents were removed promptly so stacks remained accessible.

Routine inspection supported early fault detection. Typical checks covered:

- Drums for corrosion, bulging, leaks, or missing bungs and lids.

- Chocks, dunnage, and pallets for damage or crushing.

- Racks, guards, and bollards for impact damage from trucks.

Preventive maintenance on handling equipment reduced sudden failures while drums were in motion or at height. This included brakes, wheels, hydraulic systems, and lifting attachments. Documented inspection intervals and defect tagging helped keep unsafe gear out of service. When combined with clear walkways and good lighting, these practices created a storage environment where operators could move drums with controlled effort and lower risk.

Summary: Designing Robust Drum Handling Systems

Designing a robust drum handling system means turning every step of how to move drums safely into a controlled process. The goal is simple. Avoid dropped loads, crushed operators, and loss of containment, while keeping throughput high. Engineering, operations, and EHS teams must work from the same rulebook.

The article showed that risk control starts with correct hazard identification and regulatory alignment. Labels, SDS data, zoning, and permits defined what could go wrong and where. Engineers then selected handling methods that kept forces on the body below ergonomic limits and kept loads within equipment Safe Working Load ratings. Manual handling stayed as an exception, not the norm, because full drums often weighed several hundred kilograms.

Storage and layout decisions completed the system. Stable stack geometry, conservative stack heights, and clear aisles reduced collapse and impact risks. Signage for load ratings and stack limits helped operators make the right call under pressure. Fire, explosion, and static controls protected facilities handling flammable or reactive contents, while disciplined housekeeping and inspection caught damage early.

For implementation, sites should standardize handling tools, inspection checklists, and training modules around one core question: how to move drums safely every time. Future systems will likely add more sensors, interlocks, and monitoring, but the fundamentals will not change. Clear information, engineered equipment like drum stacker, and forklift drum grabber, and repeatable procedures will remain the backbone of safe, efficient drum handling. Additionally, tools such as a drum dolly can further enhance safety and efficiency.