Facilities searching for how to lift 55 gallon drum safely must control both load hazards and operator strain. This article covers the full lifecycle of 55-gallon drum handling, from regulatory rules and storage layouts to manual techniques and engineered lifting devices.

You will see how OSHA and fire code requirements shape layouts, stacking limits, and containment systems for heavy chemical drums. The middle sections explain why manual lifting is unsafe, how to roll and tilt drums ergonomically, and how to organize team moves and work areas.

The equipment section compares barrel lifter, forklift drum grabber, and below-hook devices, including adapters for plastic and non-standard drums, with emphasis on load ratings and safe operation. The final summary links these engineering and ergonomic practices into a single, practical standard for safer 55-gallon drum handling in industrial plants and warehouses.

Core Hazards And Regulatory Requirements

Knowing how to lift 55 gallon drum loads safely starts with hazard recognition and legal duties. This section explains the main risks, OSHA rules, fire code expectations, and how storage and PPE choices control those risks. It links drum weight, chemical hazards, and layout design so engineers and safety teams can build a complete handling standard.

OSHA And fire code rules for drum handling

OSHA treated drum handling as both a material handling and hazardous materials task. A typical 55-gallon drum weighed 180 to 360 kilograms, which exceeded safe manual limits, so OSHA expected use of handling equipment. Rules prohibited pressurizing drums to remove contents and required relief paths on temporary pressurized systems. Fire codes and OSHA guidance required several controls for flammable or toxic contents.

| Requirement | Typical expectation |

|---|---|

| Location of flammable/toxic drums | Out-of-the-way area or protected by barriers |

| Containment capacity | Dikes or pans with ≥35% of stored volume |

| Stacking access | Layout that allows inspection without ladders |

| Fire protection | Suitable extinguishers in the immediate area |

| Heat sources | No storage near open flames or hot metal |

Engineers needed to check that lifting gear complied with OSHA and relevant ANSI standards for below-hook devices and overhead lifting. Facilities also had to keep aisles clear, mark safe routes, and train operators on site-specific procedures.

Chemical, flammability, and spill risk assessment

Before deciding how to lift 55 gallon drum loads, teams had to know the contents and hazards. Labels and Safety Data Sheets (SDS) identified whether liquids were corrosive, toxic, or flammable. If labels were missing, best practice treated the drum as hazardous until analysis confirmed the contents. Risk assessment considered three main aspects.

- Exposure risk: splash, vapour, or skin contact during lifting, tilting, or decanting.

- Fire and explosion risk: ignition from heat, sparks, or static near flammable liquids.

- Spill impact: volume released, drainage paths, and clean-up capability.

Assessments then set controls: containment sizing, compatible absorbents, and emergency kits near drum areas. Procedures required substance identification before spill response and ensured workers had both training and correct materials for clean-up.

Storage layouts, stacking limits, and containment

Safe layout design was critical when planning how to lift 55 gallon drum loads in warehouses and process areas. Standard guidance limited rows to two drums high and two drums wide. This limit kept inner drums visible without ladders and reduced load on lower drums of uncertain strength. Wider or higher stacks made inspection difficult and increased collapse risk.

Engineers also had to coordinate pallet patterns, floor loads, and containment. Mixed pallet counts, such as three-drum and four-drum pallets in one stack, could create uneven support and instability. For flammable or toxic liquids, dikes or pans had to hold at least 35% of the total stored volume. Layouts needed clear aisles for handling equipment, emergency access, and fire-fighting.

Floor slabs and racking systems required verification against concentrated drum loads. Design checks considered drum mass, dynamic forces from handling, and impact from lift trucks. Good layouts supported safe lifting paths, short travel distances, and controlled turning zones.

PPE selection for drum lifting and transport

PPE backed up engineering and procedural controls but did not replace them. Selection started from the SDS and the chosen lifting method. For routine drum moving and lifting, basic items included steel toe-cap safety shoes, work gloves, and eye protection. These reduced risks from crush injuries, sharp edges, and splashes during minor leaks.

Where chemicals were corrosive or toxic, facilities added chemical-resistant gloves, face shields, and protective clothing or aprons. Respiratory protection was needed if vapours, mists, or dust could form during opening, lifting, or decanting. High-visibility clothing helped keep operators visible to forklift barrel grabber and crane drivers along drum routes.

PPE programs required fit checks, regular inspection, and replacement on a defined schedule. Training had to show workers how PPE linked to specific drum hazards and tasks, such as rolling, tilting, or attaching lifting devices. This ensured PPE supported, rather than hindered, safe and ergonomic drum handling.

Manual Handling And Ergonomic Techniques

This section explains how to lift a 55-gallon drum safely without relying only on strength. It focuses on manual methods, body posture, and teamwork so operators avoid back injuries and chemical exposure. The guidance links ergonomic limits with practical field techniques for rolling, tilting, and positioning heavy drums.

Why 55-gallon drums exceed safe manual limits

A typical 55-gallon drum can weigh 180–350 kilograms when full. This load is far above common safe manual limits of about 25 kilograms for men and 16 kilograms for women. Even “empty” drums can still weigh over 20 kilograms and are bulky and hard to grip.

The forces on the body are higher than the drum weight because of awkward reaches and poor leverage. The operator often works away from the body, which increases bending moments on the spine. This raises the risk of musculoskeletal disorders, including back strain, shoulder injuries, and knee problems.

Two-person lifts do not fix the problem. Load sharing is rarely even, and one person often takes more weight during sudden shifts. For these reasons, engineers should treat full drum lifting as a mechanical handling task, not a manual lift.

Safe methods for rolling, tilting, and upending drums

Knowing how to lift a 55 gallon drum by tilting and rolling is more about technique than strength. The goal is to keep the drum under control while keeping the spine neutral.

For controlled rolling on the bottom chime:

- Stand close to the drum with feet shoulder-width apart.

- Place both hands on the far side of the top chime.

- Pull the drum toward you until it balances on the lower chime.

- Walk the drum forward, pushing with both hands and never crossing arms.

For upending from horizontal to vertical, or the reverse, use these steps:

- Crouch with knees bent, not the back.

- Grip the chime on both sides and use leg power to initiate the tilt.

- Keep the drum close to the body to reduce lever arm forces.

- Guide it slowly to the new position, never allowing a free fall.

Operators must inspect the route and floor condition first. Wet, sloped, or uneven surfaces greatly increase the chance of loss of control and impact or spill events.

Posture, body mechanics, and MSD risk reduction

Ergonomic technique is central to any method for how to lift a 55 gallon drum by hand. The spine should stay as straight as possible while the hips and knees do most of the movement. Twisting while bent forward multiplies disc loading and must be avoided.

Key posture rules include:

- Keep the drum close to the body to reduce torque on the lower back.

- Face the direction of travel instead of twisting the trunk.

- Use small steps and shift weight smoothly to avoid sudden jerks.

- Limit work above shoulder height to reduce shoulder and neck strain.

Short, repeated handling tasks can be as damaging as single heavy lifts. Engineers should design workflows that limit repetition, add micro-breaks, and rotate tasks. Training should show workers how poor posture leads to long-term joint wear, not just short-term pain.

Team handling, communication, and work area setup

Team handling is often used where space is tight or mechanical aids cannot reach. It only improves safety when communication and layout are planned. Both workers must agree on commands such as “lift,” “tilt,” “stop,” and “set down” before starting.

A good work area setup for manual drum handling includes:

- Clear, level paths free from hoses, pallets, and debris.

- Enough width to roll or tilt the drum without striking obstacles.

- Good lighting so operators see chimes, leaks, and labels.

- Marked zones that separate pedestrian routes from handling lanes.

Before any team lift or tilt, one person should act as leader and call each movement. Both workers should move in sync and avoid stepping backward blindly. Where frequent moves occur, engineers should redesign the layout to bring in drum transporter or forklift drum grabber so manual handling becomes the exception, not the rule.

Drum Lifters, Grabbers, And Below-Hook Devices

Knowing how to lift 55 gallon drum loads safely starts with the right below-hook devices. This section explains how drum lifters, grabbers, and adapters support safe overhead handling, controlled pouring, and rough-duty use. It links equipment design to OSHA and ANSI/ASME rules so engineers and supervisors can specify, inspect, and operate lifting gear with confidence.

Key design features and load rating verification

When engineers plan how to lift 55 gallon drum loads, they must match device design to drum geometry and mass. Typical below-hook drum lifters handle ribbed 55-gallon steel drums with about 57 centimetre diameter. Frames use welded structural steel for stiffness and long fatigue life under repeated lifts. Manufacturers usually qualify welds to standards such as ANSI/AWS D14.1 and design to ASME BTH-1 principles.

Safe Working Load must exceed the heaviest expected drum. Common lifters rate about 363 kilograms for full drums and 227 kilograms for partial drums. Each device should carry a clear capacity tag and identification plate. Responsible suppliers test every unit to at least 125 percent of rated load under ANSI/ASME B30.20 rules and issue a load test certificate.

Before use, supervisors should verify three points: capacity marking, test documentation, and physical condition. Technicians must check hooks, chains, and cinch mechanisms for wear, deformation, or corrosion. Any bent arms, cracked welds, or damaged teeth in the ratchet system justify immediate removal from service. A simple checklist and inspection log help maintain traceability and regulatory compliance.

Using below-hook drum lifters and tilt locks safely

Below-hook drum lifters answer the core question of how to lift 55 gallon drum loads while also rotating and pouring. Many units allow 360-degree manual rotation for controlled dispensing. The drum sits in a holder that engages between ribs, then a cinch chain and ratchet clamp the shell. Operators tighten the chain without tools, which reduces setup time and avoids over-torquing.

Tilt locks on the frame secure the drum at key angles. Typical positions include vertical, horizontal, and about 45 degrees up or down. This feature prevents unplanned rotation during travel or while suspended. Operators should always confirm the lock pin or latch is fully engaged before lifting clear of the floor.

Safe use follows a simple sequence:

- Inspect drum and lifter for leaks, damage, and rating compliance.

- Attach the lifter to the crane hook with the hook latch closed.

- Center the device over the drum and engage the holder between ribs.

- Tighten the cinch chain evenly, then test by slightly raising the drum.

- Set the tilt angle with the lock, then lift only high enough for travel.

Operators should avoid sudden starts, stops, or side pulls, which increase sling and frame loads. Training must stress that nobody stands under or near the suspended drum path. Drums must never remain unattended while hanging; always lower to a stable surface before leaving the area.

Overhead drum grabbers and rough-duty applications

Overhead drum grabbers suit harsher environments where drums move quickly or where floor space is limited. These grabbers often use a three-arm design that centres the drum under the lifting point. The arms grip the drum chime and work with both closed-head and open-head steel drums, within stated limits. Typical capacity ratings reach about 1,000 kilograms for closed-head drums and 500 kilograms for open-head drums.

Arms usually use ductile iron for strength and impact resistance. A spring-loaded polyurethane loop or similar feature adds redundancy by holding the arms in position. This reduces the chance of accidental release during minor impacts or vibration. However, operators still need to manually disengage the grabber once the drum rests on the ground or pallet.

Rough-duty applications include scrap yards, foundries, and chemical plants with heavy crane use. In these locations, engineers should specify grabbers with generous safety factors and robust arm pivots. Regular inspection intervals must be shorter due to higher cycle counts and shock loading. Key checks include arm wear at contact points, spring function, and correct movement of all pivots.

Supervisors should define clear operating envelopes. Examples include no side pulling, no dragging drums along the floor, and no lifting of visibly damaged drums. Combining overhead grabbers with good storage layouts and guarded travel paths lowers collision risk and protects both drums and structures.

Adapters for plastic, fiber, and non-standard drums

Not every site handles only standard steel drums, so adapters are central to any plan for how to lift 55 gallon drum variants. Rimless plastic and fibre drums cannot rely on chime grabs alone. Bracket assemblies wrap around the drum body and support it from below. Typical designs adjust for drum heights between about 78.7 and 99 centimetres.

Diameter adapters let one lifter handle smaller drums, often from 35.6 to 55.9 centimetres diameter. Some models integrate end brackets that support the drum bottom and prevent slip during tilt. This design is important when rotating light plastic drums, which deform more easily than steel. Adapters must lock positively to the main frame so they cannot detach in mid-lift.

When selecting adapters, engineers should consider:

| Parameter | Engineering concern |

|---|---|

| Drum material | Shell stiffness and risk of crushing |

| Presence of rim | Need for full-height bracket support |

| Height range | Adjustment travel and clamping reach |

| Diameter range | Contact area and grip stability |

| Chemical compatibility | Corrosion and seal material selection |

Each adapter set should carry its own rated capacity, which may be lower than the base lifter. Procedures must state the reduced limit clearly. Training should show operators how to fit adapters, confirm locking pins, and check that the drum cannot shift before lifting. This structured approach lets one lifting system handle mixed drum fleets without sacrificing safety or ergonomics.

Summary: Safer, Ergonomic 55-Gallon Drum Handling

Facilities that search for how to lift 55 gallon drum safely need a full-system view. Safe handling links load rating, ergonomics, and chemical risk control into one procedure. A typical 55-gallon drum can weigh 180–350 kilograms, so manual lifting is not acceptable. Mechanical aids, engineered lifters, and trained operators are the core controls.

Key findings show that manual handling must stay below accepted limits, while drums far exceed those values. Below-hook lifters, drum grabbers, and tippers with verified Safe Working Load and ANSI/ASME compliance give predictable safety margins. OSHA rules require secure storage, spill containment for large flammable drums, and protection from impact and heat sources. Good layouts keep stacks low, aisles open, and leaks visible.

In practice, sites should standardize pre-use checks, drum inspection, and PPE for every lift and move. Operators need clear methods for rolling, tilting, and upending drums with minimum spinal load. Equipment such as overhead grabbers and tilt-lock lifters must follow strict inspection and maintenance plans. Training should cover ATEX controls, emergency spill response, and realistic case studies.

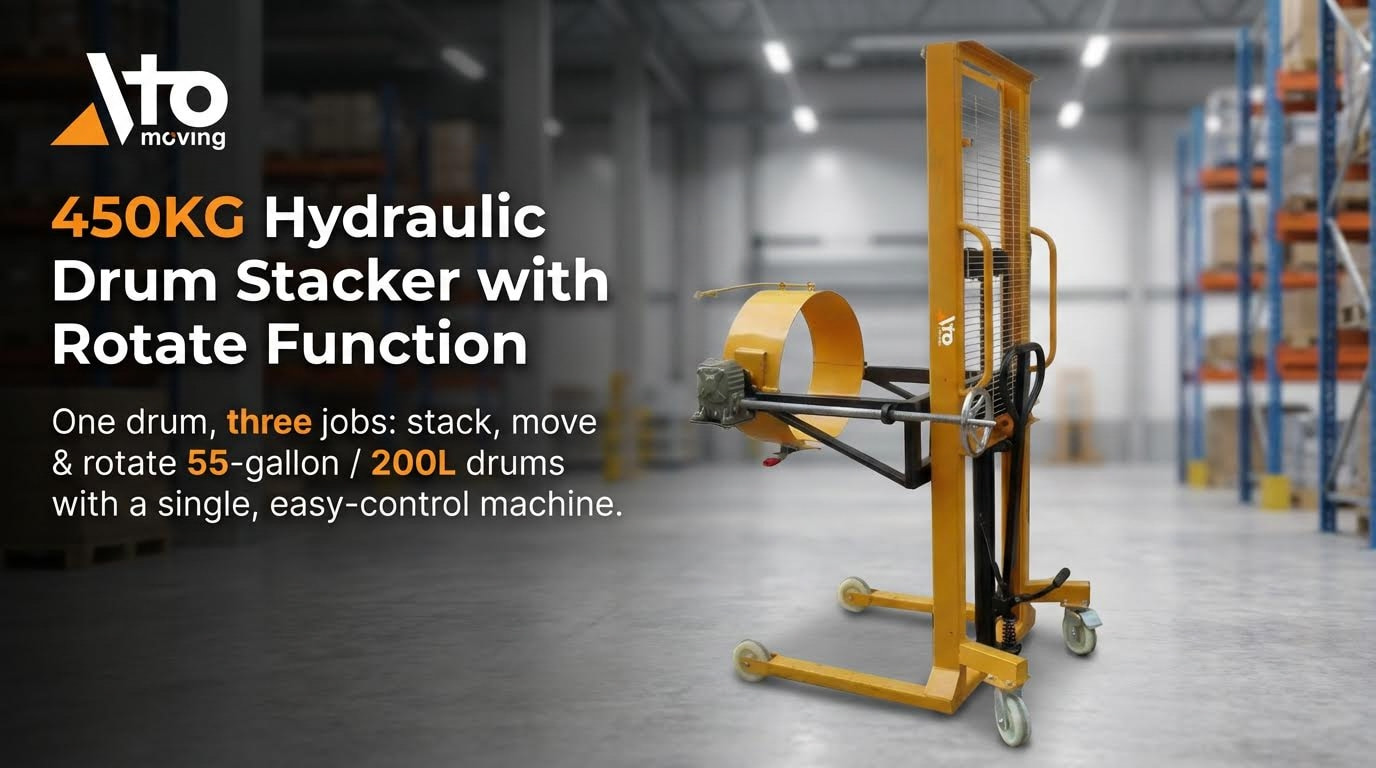

Looking ahead, safer drum handling will combine better ergonomics, smarter lifting devices, and digital inspection records. The goal is consistent control of high-mass loads without over-reliance on operator strength or experience. Plants that align engineering, safety, and operations around one written standard for drum handling will see fewer injuries and more stable throughput. For facilities handling multiple drums, solutions like the hydraulic drum stacker or drum dolly provide efficient and safe options.